- Container Networking Is Simple!

- What Actually Happens When You Publish a Container Port

- How To Publish a Port of a Running Container

- Multiple Containers, Same Port, no Reverse Proxy...

- Service Proxy, Pod, Sidecar, oh my!

- Service Discovery in Kubernetes: Combining the Best of Two Worlds

- Traefik: canary deployments with weighted load balancing

Don't miss new posts in the series! Subscribe to the blog updates and get deep technical write-ups on Cloud Native topics direct into your inbox.

If you're dealing with containers regularly, you've probably published ports many, many times already. A typical need for publishing arises like this: you're developing a web app, locally but in a container, and you want to test it using your laptop's browser. The next thing you do is docker run -p 8080:80 app and then open localhost:8080 in the browser. Easy-peasy!

But have you ever wondered what actually happens when you ask Docker to publish a port?

In this article, I'll try to connect the dots between port publishing, the term apparently coined by Docker, and a more traditional networking technique called port forwarding. I'll also take a look under the hood of different "single-host" container runtimes (Docker Engine, Docker Desktop, containerd, nerdclt, and Lima) to compare the port publishing implementations and capabilities.

As always, the ultimate goal is to gain a deeper understanding of the technology and get closer to becoming a power user of containers. Let the diving begin!

What is Port Forwarding aka Port Mapping

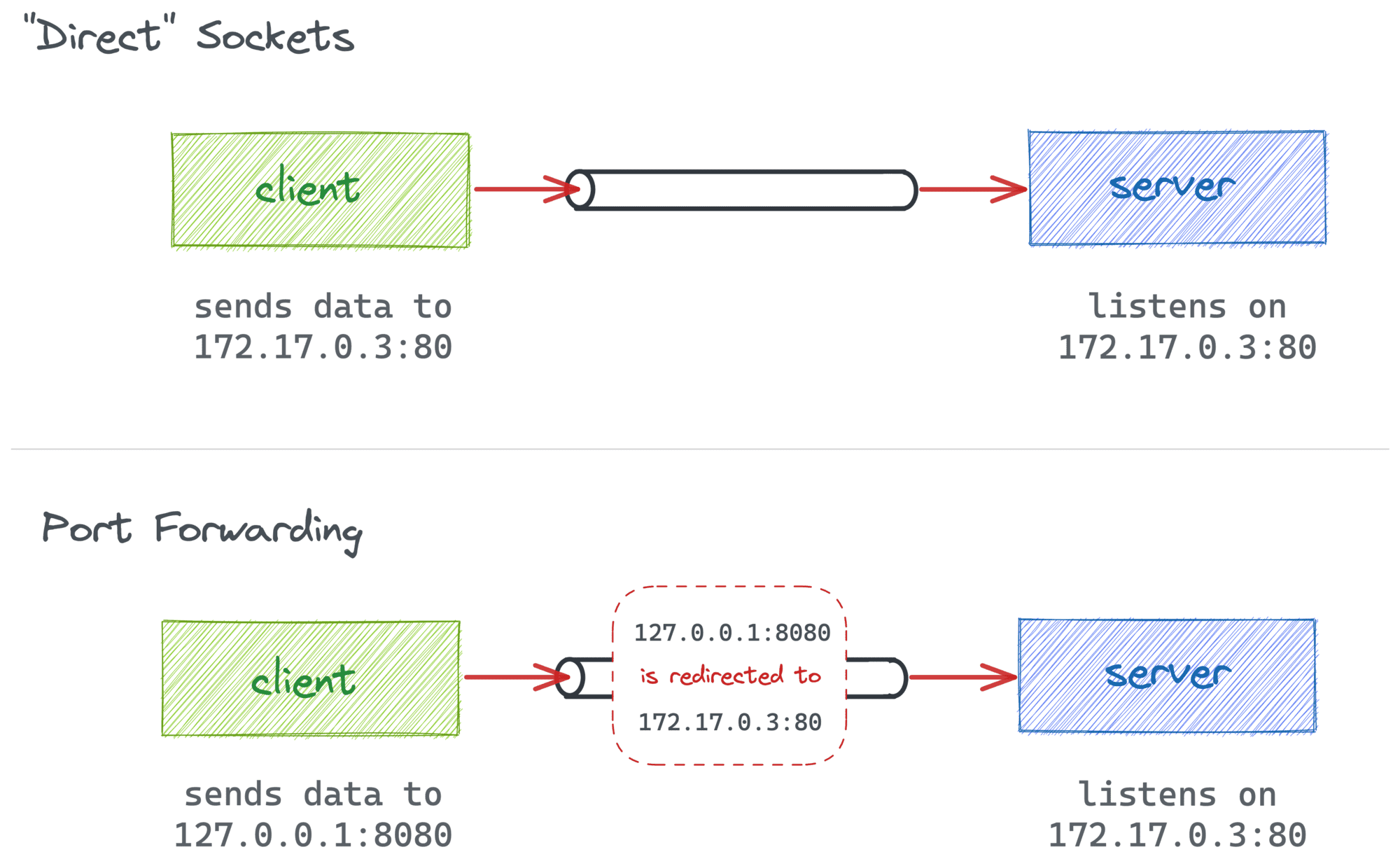

Ports aren't a thing on their own. When we say port we usually refer to a certain [Internet] socket address defined by a pair of IP address and port number.

Sockets are meant to represent the participants of a network data exchange. So, port forwarding or, as it's also called, port mapping is just a fancy way to say that data addressed to one socket is redirected to another by an intermediary (for instance, by a network router or a proxy process).

🤓 Technically, port forwarding is a form of Network Address Translation (NAT).

There are two common ways to redirect network data (hence, implement port forwarding):

- By sneakily modifying the destination address of packets.

- By explicitly putting a proxy between the client and the server.

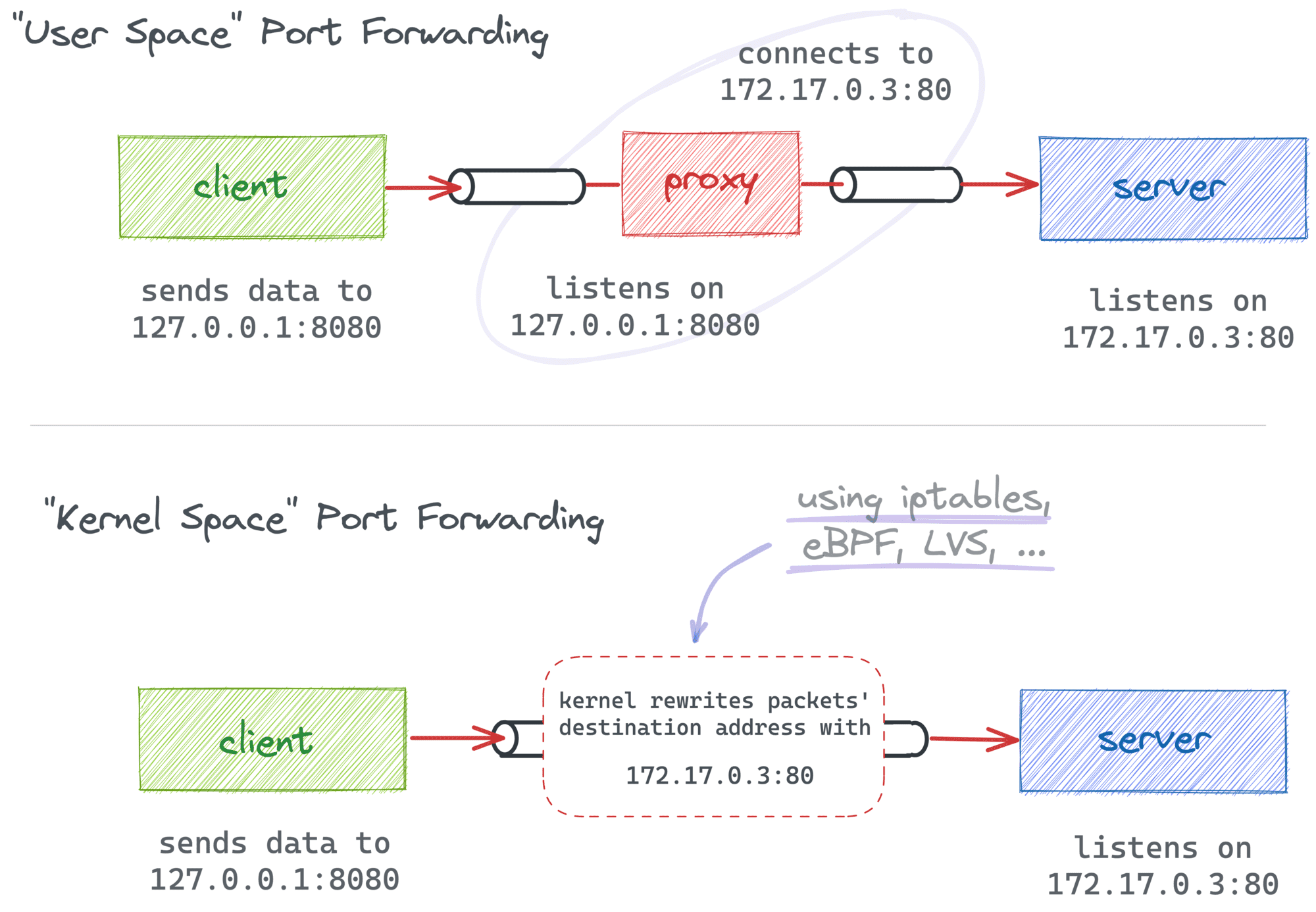

In the first case, packets originally destined to some <addr1:port1> get modified (or translated) on their way and instead delivered to <addr2:port2>. Often, this is done by a Linux kernel component such as netfilter configured with a bunch of iptables rules.

In the second case, the client-facing socket is actually maintained by an L4+ proxy process that reads the incoming data and re-sends it to the final destination. I.e., no packets are actually translated, and only the payload data is proxied.

While there is a subtle difference between the two methods, most of the time, they are interchangeable:

But why the rant?

Because I think that understanding the idea behind port forwarding and the most common ways to implement it is vital for the in-depth discussion of why and how to publish container ports.

Containers and Port Forwarding

Normally, a container has its own network stack and IP address. Being able to access that IP address allows you to call any services running inside of the container (assuming they listen on the container's public interface).

For instance, with Docker Engine on Linux (not to be confused with Docker Desktop that also supports Linux since May 2022), you can create an nginx container and curl it from the host:

$ docker run -d --name nginx-1 nginx

$ CONT_IP=$(

docker inspect -f '{{range.NetworkSettings.Networks}}{{.IPAddress}}{{end}}' nginx-1

)

$ curl $CONT_IP:80

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Welcome to nginx!</title>

...

You can even open the above address in your favorite browser if you're brave enough to run containers on your main system. This is a handy capability, and I often rely on it while performing some ad-hoc tasks. But is it any good for real use?

Well, I'm aware of at least two significant "inconveniences" of accessing Docker containers by their IPs:

- Container IPs are assigned dynamically, and the container's restart (or rather recreation) may cause its IP address to change.

- By default, container IPs are routable only from the inside of the host and inaccessible from the outside world.

And that's where port publishing comes in handy!

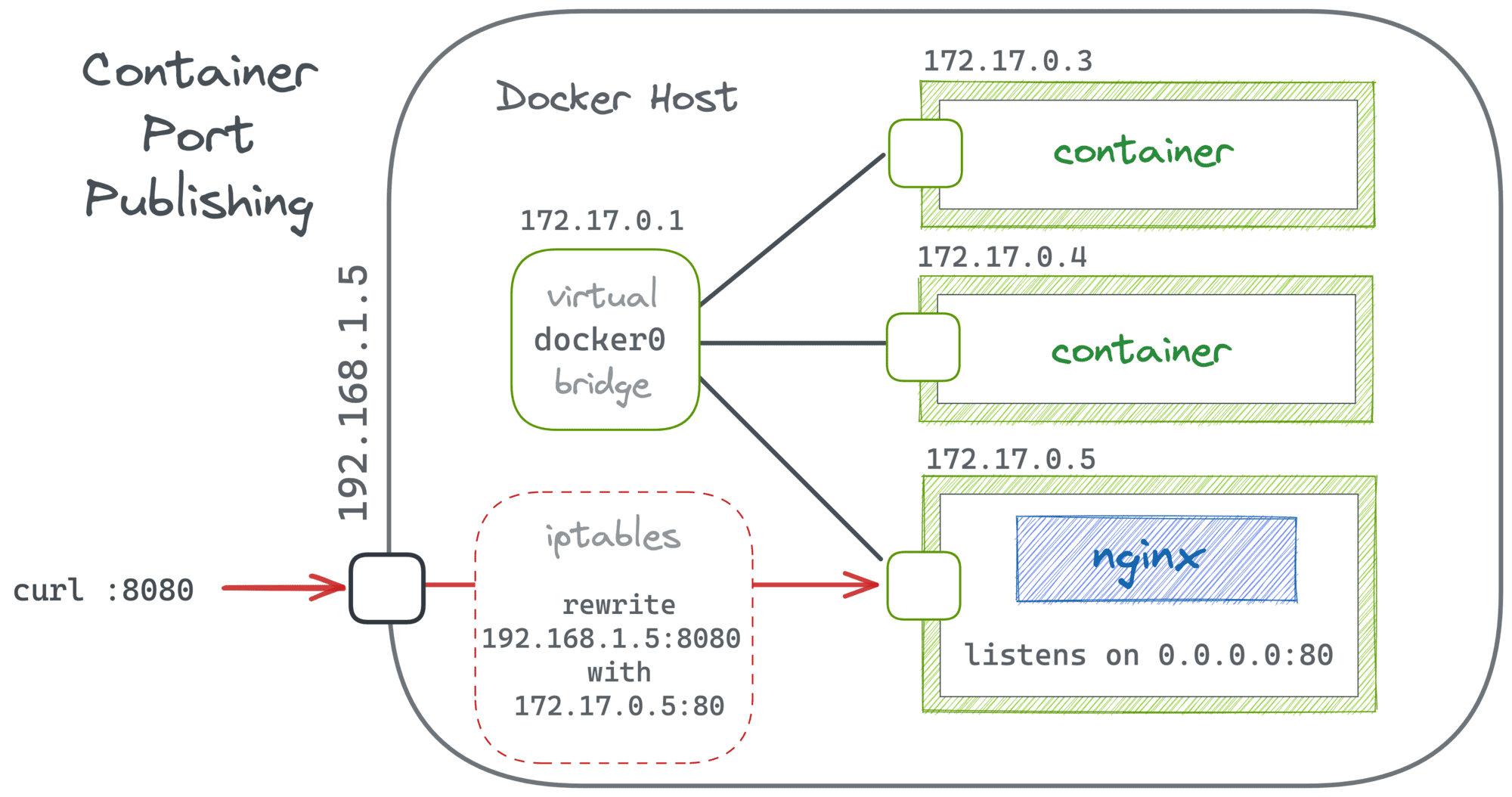

In its simple form, the docker run --publish 8080:80 nginx command creates a regular port forwarding from the host's 0.0.0.0:8080 to the container's $CONT_IP:80.

Since both sides of the mapping reside on one Linux host, such a forwarding can be implemented with just a couple of iptables rules:

$ docker run -d -p 8080:80 --name nginx-1 nginx

$ sudo iptables -t nat -L

...

Chain POSTROUTING (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

...

MASQUERADE tcp -- 172.17.0.2 172.17.0.2 tcp dpt:http

Chain DOCKER (2 references)

target prot opt source destination

...

DNAT tcp -- anywhere anywhere tcp dpt:8080 to:172.17.0.2:80

👉 See this section of my practical explanation of container networking for the complete example.

Thus, it seems that in the case of Docker Engine, there is not much difference between port publishing and good old kernel space port forwarding. The only "extra" functionality that Docker adds on top is the automatic update of the destination part of the mapping in the case of the container's IP address change.

💡 You probably know that docker run --publish allows specifying the host's interface explicitly, but did you also know that Docker supports port ranges with 8080-8090 syntax?

docker run --publish 127.0.0.1:8080-8090:80 nginx

Port Publishing and Different Network Drivers

The experiment in the section above was done using the default (bridge) network driver. Clearly, bridge-based networks support and benefit from port publishing. However, Docker has a few other network types. In Docker's own words:

The type of network a container uses, whether it is a

bridge, anoverlay, amacvlannetwork, or a custom network plugin, is transparent from within the container. From the container's point of view, it has a network interface with an IP address, a gateway, a routing table, DNS services, and other networking details (assuming the container is not using thenonenetwork driver).

But does the type of network affects the port publishing capabilities?

Let's review every network type one by one:

nonenetwork means there is no external network interface (hence, no IP address), and only the loopback exists in the container. Well, no IP address - no port forwarding.hostnetwork means the container doesn't have its own network stack. Instead, it reuses the host's one. You still can forward ports, but you'll have to do it by yourself (for instance, by manually creating iptables rules) because, from Docker's standpoint, there is very little need for it.container:<other>network means the current container reuses the network mode of another container. In particular, it makes the container inherit the already published ports (if any). But you cannot publish your own ports in that mode.overlaynetwork seems to be an echo of the Swarm days. Apparently, you can do some sort of port publishing there, but for "services" and not individual containers. Don't have much experience with this mode, so won't speculate.ipvlanandmacvlannetwork modes don't support port forwarding because they probably assume that IP addresses assigned to containers are directly routable and fall out of basic Docker's responsibilities.

To summarize, the only network type you'll want to use port publishing with is bridge. But this is the default and probably the most widespread type, so this limitation doesn't diminish the value of port publishing much.

⚠️ Note that most of the time, Docker will silently ignore the -p|--publish flag if the underlying network driver doesn't support port forwarding.

Docker Desktop and Port Publishing

Surprisingly or not, Docker Desktop's behavior differs from Docker Engine's when it comes to container networking. Here is what happens when I try to access a container by its IP address on my MacBook:

$ docker run -d --name nginx-1 nginx

$ CONT_IP=$(

docker inspect -f '{{range.NetworkSettings.Networks}}{{.IPAddress}}{{end}}' nginx-1

)

$ ping $CONT_IP

PING 172.17.0.3 (172.17.0.3): 56 data bytes

Request timeout for icmp_seq 0

Request timeout for icmp_seq 1

^C

--- 172.17.0.3 ping statistics ---

3 packets transmitted, 0 packets received, 100.0% packet loss

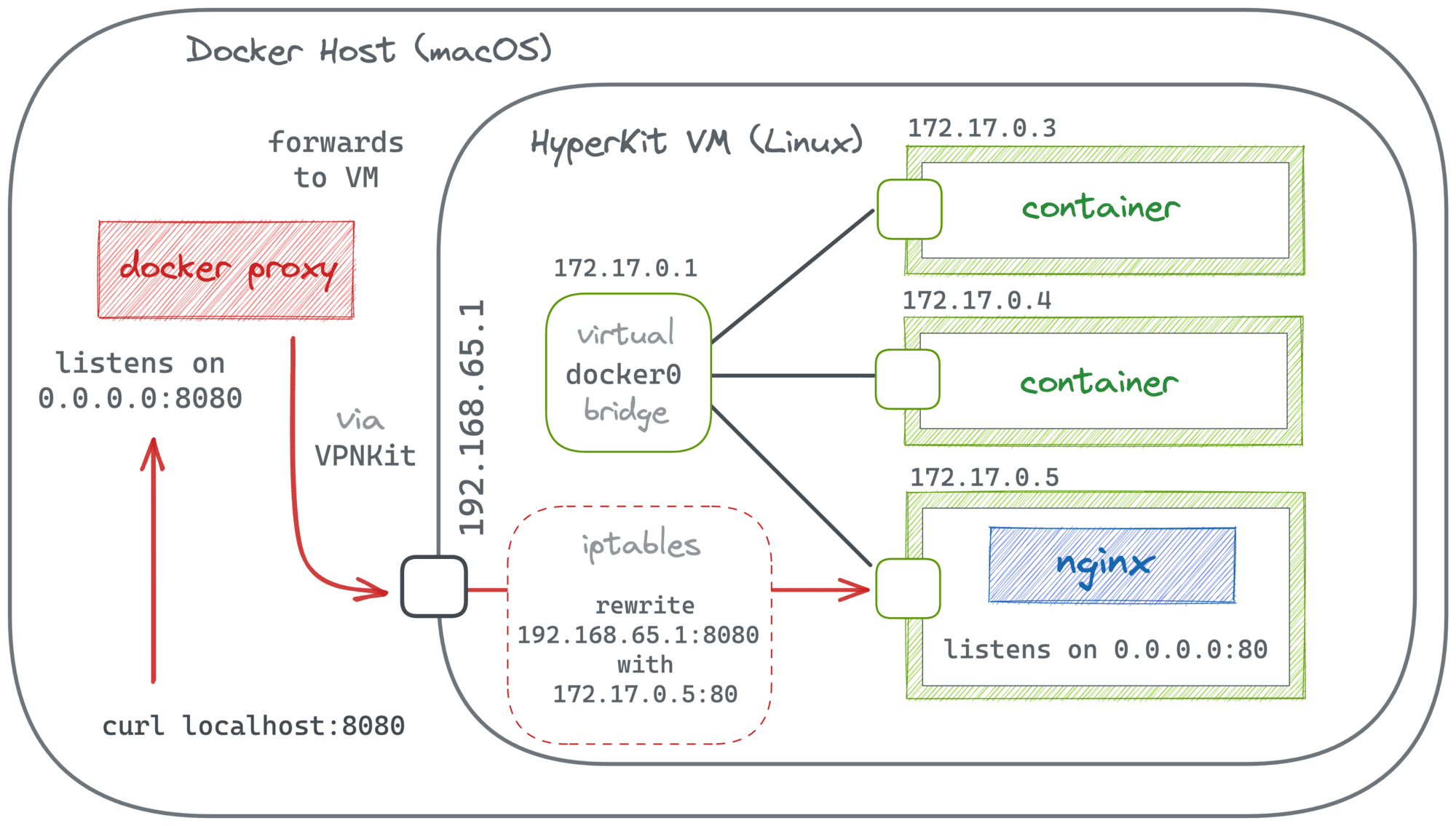

Well, it kind of makes sense. Docker containers require a Linux kernel. So, Docker Desktop for Mac (and likely for Windows and Linux as well) sneakily starts a full-blown virtual machine running a custom Linux distro with pre-installed Docker Engine. Therefore, the above 172.17.0.3 address is an address from a bridge network that exists only inside that virtual machine. Evidently, it's not routable from the host system (macOS, in my case).

But nevertheless, port publishing works in Docker Desktop!

$ docker run -d -p 8080:80 --name nginx-1 nginx

$ curl localhost:8080

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Welcome to nginx!</title>

...

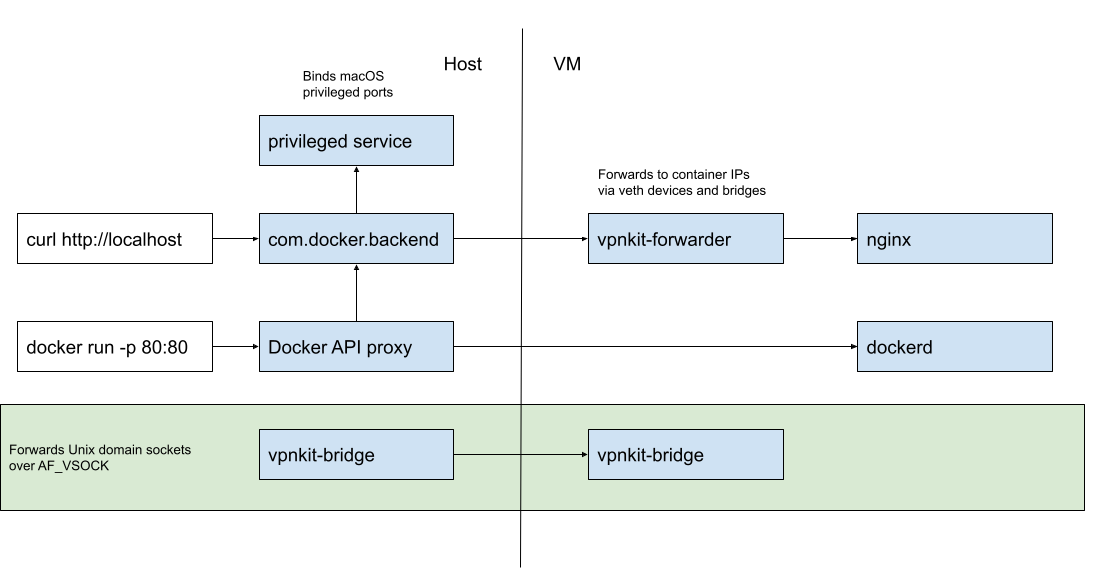

The implementation of port publishing in Docker Desktop had been remaining puzzling for me until relatively recently. But then David Scott published (no pun intended) a great article explaining the internals of Docker Desktop networking. In particular, it sheds some light on how port forwarding is done:

To cut a long story short, in the case of Docker Desktop, it's a combination of user space-based and traditional iptables-based port forwarding. When you start a container that publishes a port, a proxy process on the host (e.g, on macOS) opens a real socket using the specified IP address and port. You can pinpoint this process with lsof:

$ docker run -d -p 8080:80 --name nginx-1 nginx

$ sudo lsof -i -P | grep LISTEN | grep :8080

com.docke... 24294 iximiuz 76u IPv6 0x89404e558d90602b 0t0 TCP *:8080 (LISTEN)

$ ps 24294

PID TT STAT TIME COMMAND

24294 ?? S 38:09.83 /Applications/Docker.app/Contents/MacOS/com.docker.backend -watchdog -native-api

Inside the VM, the implementation of port publishing seems to be no different from the one described in the Docker Engine section of this article. It can be verified using a privileged container running in the VM's network namespace (the --net host flag because for Docker Engine the VM is the host):

$ docker run --privileged --net host -it --rm alpine

/ $# apk add iptables

/ $# iptables -t nat -L

<typical Docker Engine port forwarding iptables rules>

And the mysterious vpnkit-bridge (part of the VPNKit project) helps cross the borders between the host and the VM systems.

Summarizing, when you publish a port in Docker Desktop:

- The

com.docker.backendprocess on the host system starts acting as a user space proxy and opens a socket using the specified address. - This socket can be used by anyone on the host (or with access to the host's network) to send data to the container.

- When data appears on the socket, it gets forwarded by vpnkit-bridge to the VM's external network interface.

- Inside the VM, the container's port has already been published to that interface using the "standard" for Docker Engine iptables-based technique.

How To Publish Ports With containerd

It's no secret that Docker heavily relies on containerd for lower-level container management. But the exact separation of concerns may not always be clear. For instance, publishing ports always sounded pretty low-level to me. But it turns out that containerd cannot publish ports on its own!

Similarly to docker run --name nginx-1 nginx:latest, you can run a container directly in containerd using ctr run docker.io/library/nginx:latest nginx-1. But there is no equivalent for the -p flag. Like at all 🙈

So, port publishing is evidently one of Docker's own responsibilities. But there still might be a way...

Port Forwarding With Mighty nerdctl

nerdctl is a popular CLI client for containerd. Unlike the minimalistic ctr, nerdctl tries to be feature-rich and Docker-compatible (meaning it mimics the docker CLI commands). But if it's Docker-compatible, it must be implementing port publishing!

A quick check of the nerdctl source code revealed (cmd/nerdctl/run.go, ocihook/ocihook.go) that it relies on an OCI Runtime lifecycle hook (on "CreateRuntime" to be precise) to set up some extra networking capabilities of to-be-started containers. But nerdctl doesn't do the actual networking configuration on its own. Instead, it uses the helper containerd/go-cni package that, in particular, allows to configure port mapping (most likely also delegating the actual job to the corresponding portmap CNI plugin).

🤓 Note that the above mechanism is used only for extra configuration like port forwarding. The actual creation of the container's network namespace and its attachment to a bridge network is done by containerd itself (although likely by means of runc the underlying lower-level container runtime and/or the same containerd/go-cni helper package).

A tiny experiment to verify the above findings shows that the portmap CNI plugin uses the already familiar iptables trick to implement port forwarding. So, indeed, nerdctl stays very close to what Docker Engine does in this particular case:

$ sudo nerdctl run -d --name nerd-nginx-1 -p 8080:80 nginx

$ sudo nerdctl inspect \

-f '{{range.NetworkSettings.Networks}}{{.IPAddress}}{{end}}' \

nerd-nginx-1

10.4.0.4

$ sudo iptables -t nat -L | grep '10.4.0.4'

CNI-6603d34f605da0cf8e0a0934 all -- 10.4.0.4 anywhere

DNAT tcp -- anywhere anywhere tcp dpt:http-alt to:10.4.0.4:80

How Lima Implements Port Forwarding

The Lima project is an attempt to pack containerd with nerdctl and make the bundle run easily on macOS. Expectedly, this should involve running a virtual machine:

Lima launches Linux virtual machines with automatic file sharing and port forwarding (similar to WSL2), and containerd.

Thus, architecturally, Lima is somewhat similar to Docker Desktop.

$ limactl start

$ nerdctl.lima run -d --name lima-nginx-1 -p 8080:80 nginx

$ curl localhost:8080

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Welcome to nginx!</title>

...

Ok, publishing container ports works in Lima. But how is it implemented?

$ sudo lsof -i -P | grep LISTEN | grep :8080

ssh 86663 iximiuz 15u IPv4 0xcf4f91a867ed7809 0t0 TCP localhost:8080 (LISTEN)

$ ps 86663

PID TT STAT TIME COMMAND

86663 ?? Ss 0:00.02 ssh: /Users/iximiuz/.lima/default/ssh.sock [mux]

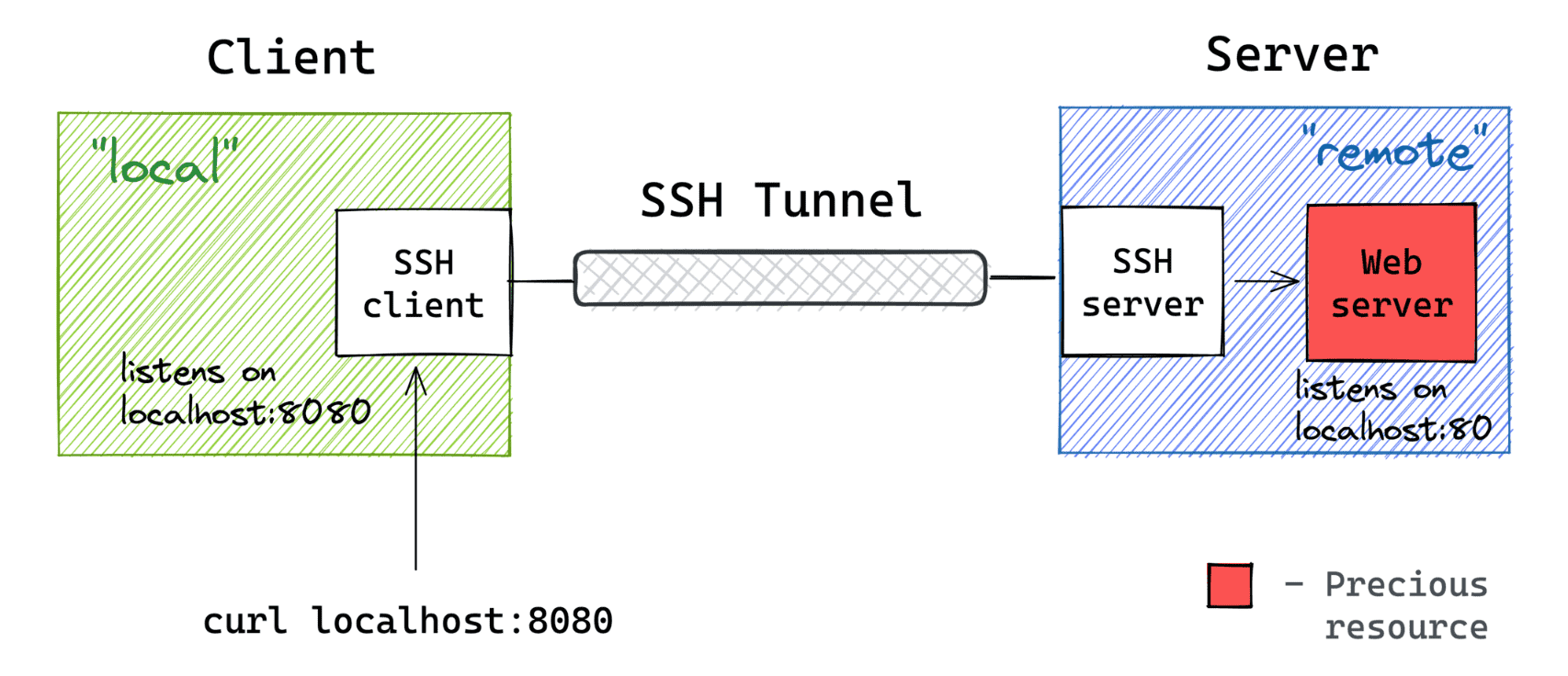

And I absolutely love what I found there! Lima uses good old SSH tunnels to forward ports between the host system (macOS) and services in the VM.

Image from my Visual Guide To SSH Tunnels.

Inside the VM, it's just a regular container (started by nerdctl) with its port published to 0.0.0.0:

$ limactl shell default

$ nerdctl ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

6f2aa0304e4c nginx:latest "/docker-entrypoint.…" 5 seconds ago Up 0.0.0.0:8080->80/tcp lima-nginx-1

It's LEGO bricks all the way down... 👷

Instead of Conclusion

So, is there a real difference between port publishing and port forwarding? Or is port publishing just a Docker's way to call port forwarding for containers? Well, you tell me 😉

In any case, understanding what actually happens when you publish a container's port is helpful. For instance, it allows you to predict what use cases will be technically feasible and enables implementation of some rather advanced scenarios like publishing ports of an already running container or accessing services listening on the container's localhost.

- Container Networking Is Simple!

- What Actually Happens When You Publish a Container Port

- How To Publish a Port of a Running Container

- Multiple Containers, Same Port, no Reverse Proxy...

- Service Proxy, Pod, Sidecar, oh my!

- Service Discovery in Kubernetes: Combining the Best of Two Worlds

- Traefik: canary deployments with weighted load balancing

Don't miss new posts in the series! Subscribe to the blog updates and get deep technical write-ups on Cloud Native topics direct into your inbox.