Why and How to Use containerd From Command Line

containerd is a high-level container runtime, aka container manager. To put it simply, it's a daemon that manages the complete container lifecycle on a single host: creates, starts, stops containers, pulls and stores images, configures mounts, networking, etc.

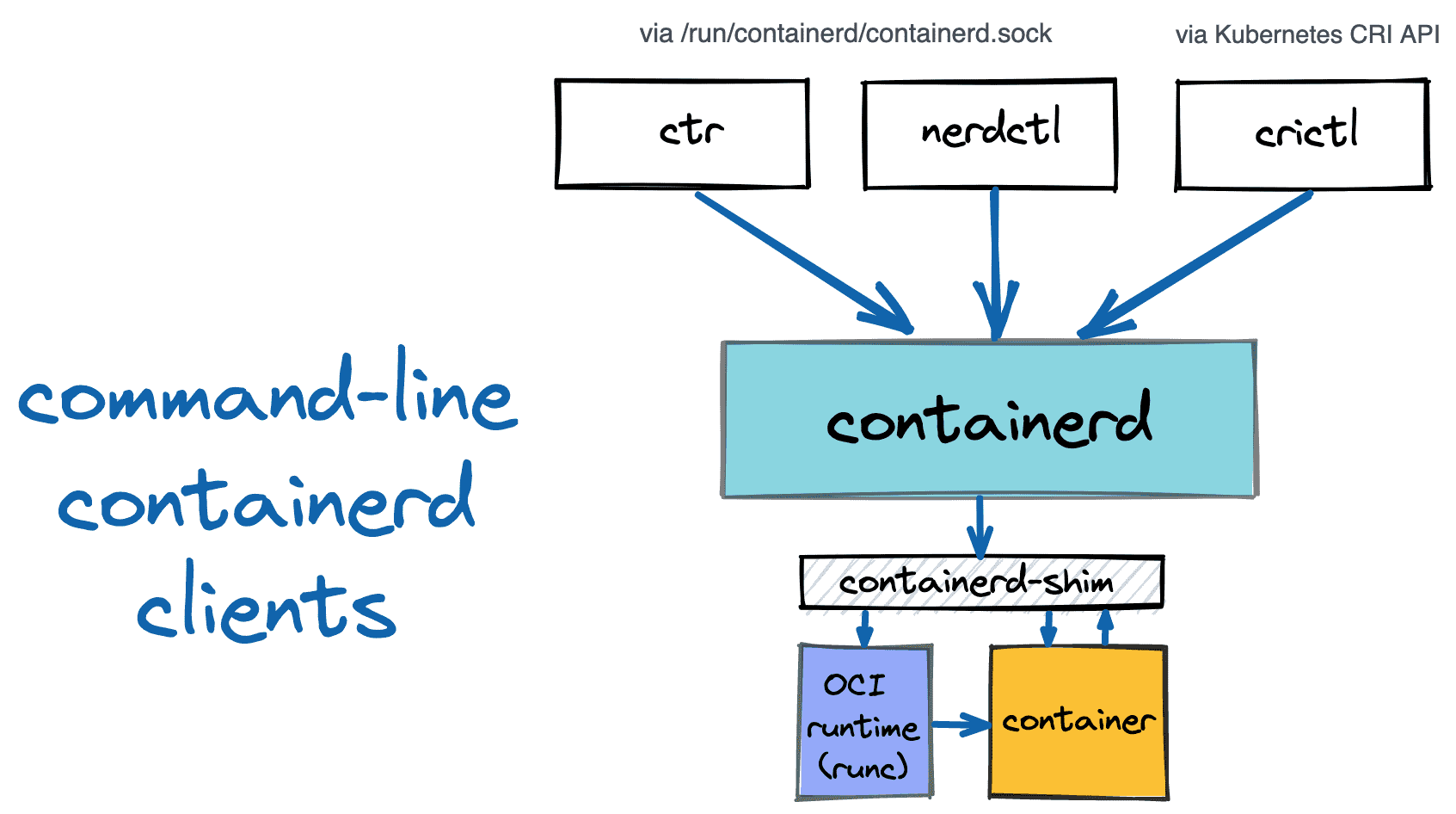

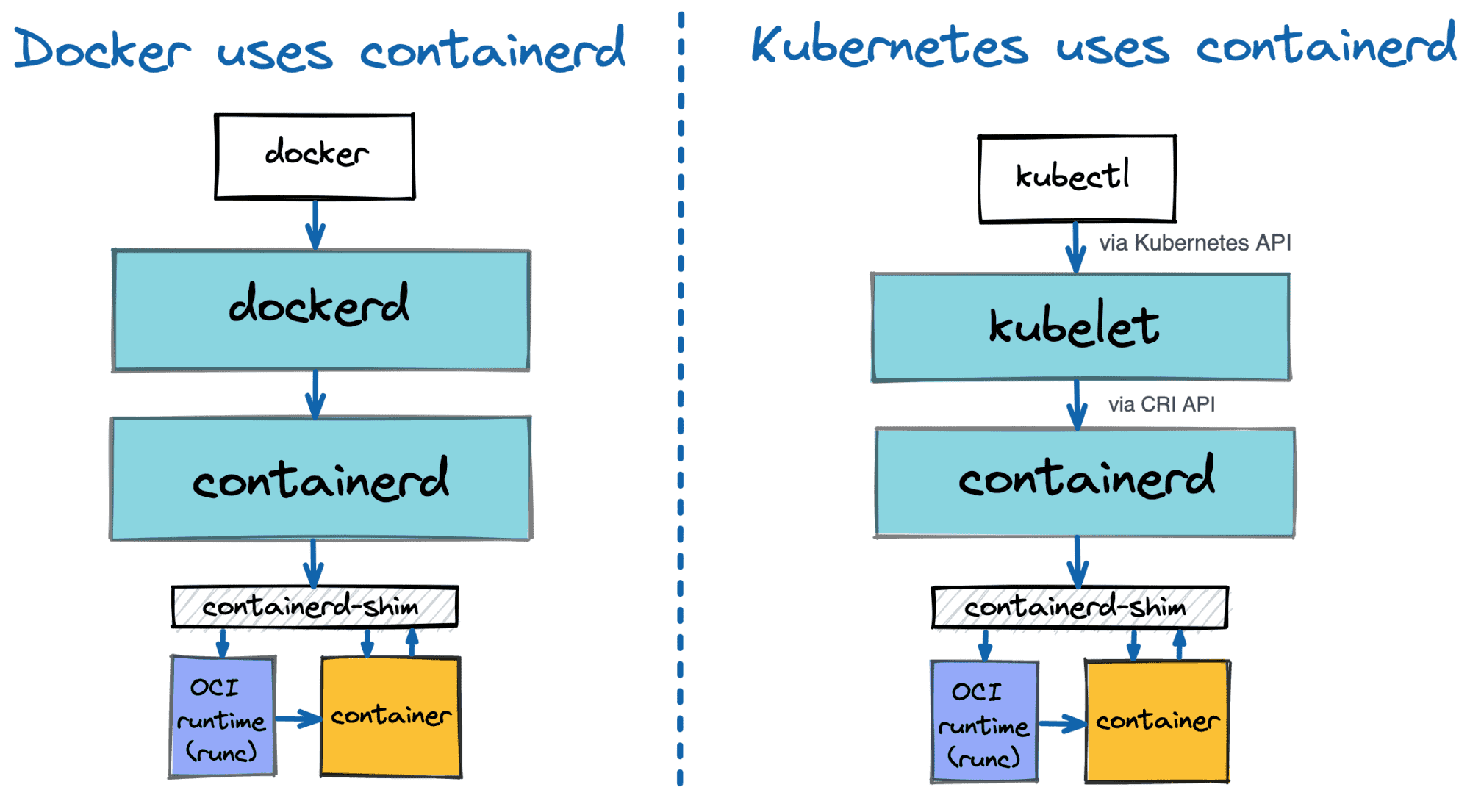

containerd is designed to be easily embeddable into larger systems. Docker uses containerd under the hood to run containers. ubernetes can use containerd via CRI to manage containers on a single node. But smaller projects also can benefit from the ease of integrating with containerd - for instance, faasd uses containerd (we need more d's!) to spin up a full-fledged Function-as-a-Service solution on a standalone server.

However, using containerd programmatically is not the only option.

It also can be used from the command line via one of the available clients.

The resulting container UX may not be as comprehensive and user-friendly as the one provided by the docker client,

but it still can be useful, for instance, for debugging or learning purposes.