- Not Every Container Has an Operating System Inside

- You Don't Need an Image To Run a Container

- You Need Containers To Build Images

- Containers Aren't Linux Processes

- From Docker Container to Bootable Linux Disk Image

Don't miss new posts in the series! Subscribe to the blog updates and get deep technical write-ups on Cloud Native topics direct into your inbox.

As we already know, containers are just isolated and restricted Linux processes. We also learned that it's fairly simple to create a container with a single executable file inside starting from scratch image (i.e. without putting a full Linux distribution in there). This time we will go even further and demonstrate that containers don't require images at all. And after that, we will try to justify the actual need for images and their place in the containerverse.

How to Run Containers without Docker and... Images

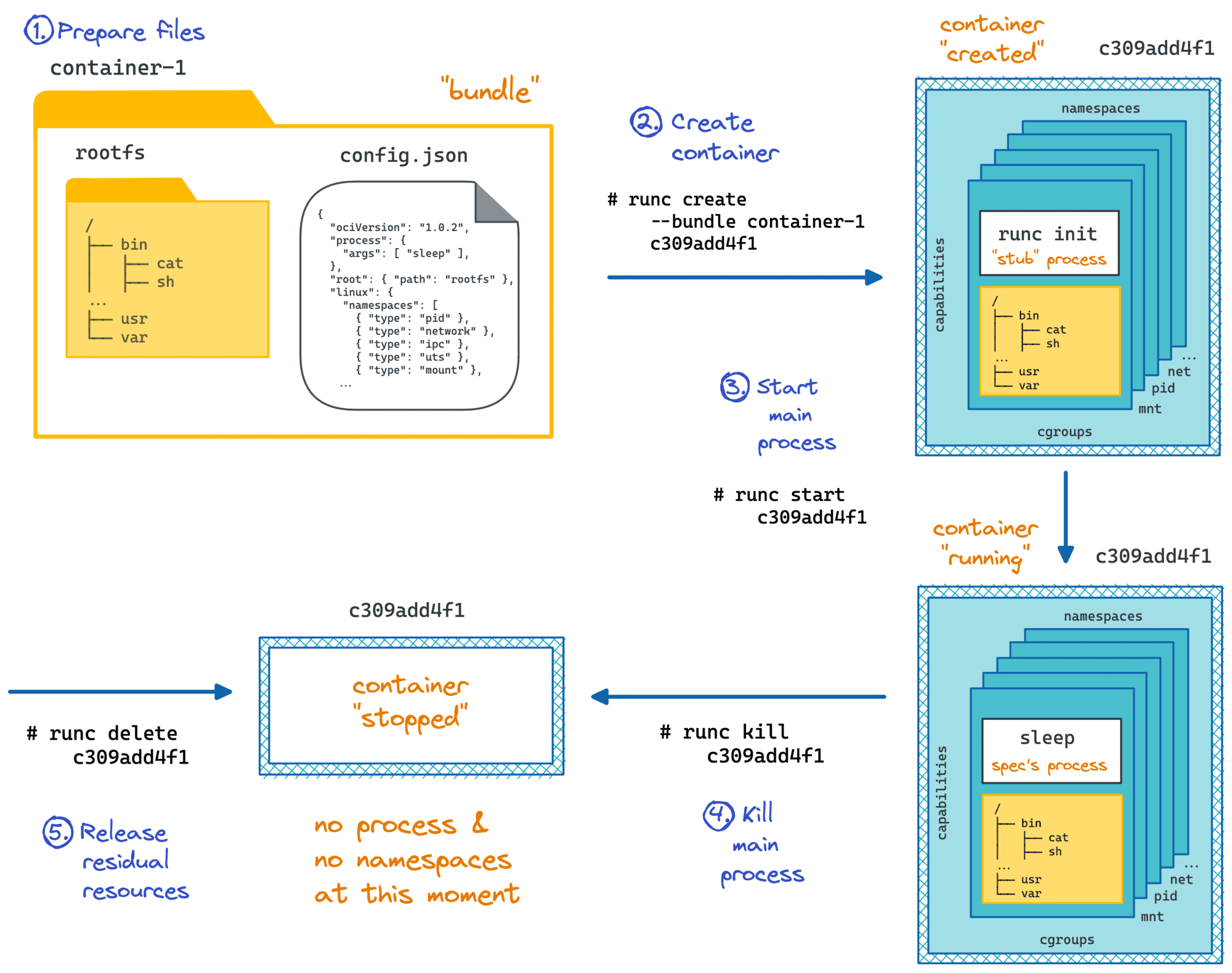

You may have heard that Docker uses a tool called runc to run containers. Well, to be more accurate, Docker depends on a lower-level piece of software called containerd which in turn relies on a standardized container runtime implementation. And in the wild, most of the time runc plays the role of such a component.

Let's take a closer look at runc. Surprisingly or not, it's a command-line tool for running containers. Following the instructions from its README file, we can come up with the sequence of commands needed to create and then start a container.

First, we need to create a container configuration file:

$ mkdir my_container && cd my_container

$ runc spec

$ file config.json

> config.json: ASCII text

The content of config.json on my machine looks as follows:

{

"ociVersion": "1.0.1-dev",

"process": {

"terminal": true,

"user": {

"uid": 0,

"gid": 0

},

"args": [

"sh"

],

"cwd": "/",

"env": [ ... ],

"capabilities": { ... },

"rlimits": [ ... ]

},

"root": {

"path": "rootfs",

"readonly": true

},

"hostname": "runc",

"mounts": [ ... ],

"linux": {

"namespaces": [

{ "type": "pid" },

{ "type": "network" },

{ "type": "ipc" },

{ "type": "uts" },

{ "type": "mount" }

]

}

}

It's not so hard to notice, that this file describes the program to be launched inside of the container (process.args[0]), its environment (env, capabilities, root filesystem, etc), and the container itself (mounts, namespaces, etc).

Now, we need to prepare a root filesystem for our container. To keep it simple, we will just start with an empty folder and put a single (statically-linked) executable in there:

$ cat <<EOF > main.go

package main

import "fmt"

import "os"

func main() {

fmt.Println(os.Hostname())

}

EOF

$ GOOS=linux GOARCH=amd64 go build -ldflags="-w -s" -o printme

$ file printme

> printme: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), statically linked, stripped

$ mkdir rootfs

$ mv printme rootfs/

We also need to modify the config.json accordingly by setting process.args[0] to /printme, disabling terminal support, and changing the hostname to something more pleasing to the eye.

Finally, we can create the container using the adjusted config.json and start it:

$ sudo runc create mycont1

$ sudo runc start mycont1

> HAL-9000 <nil>

That was it! We ran a process inside of a container and from its point of view, the hostname was HAL-9000 while running /usr/bin/hostname on this machine outside of a container gives localhost.localdomain. Pretty simple, right?

Click here to see how to run a container with a full Linux distro inside.

The procedure is exactly the same as above. The only difference is that we need to have a root filesystem of the desired Linux distribution beforehand.

$ mkdir my_container2 && cd my_container2

$ wget https://github.com/alpinelinux/docker-alpine/raw/c5510d5b1d2546d133f7b0938690c3c1e2cd9549/x86_64/alpine-minirootfs-3.11.6-x86_64.tar.gz

$ mkdir rootfs

$ tar -C rootfs -xvf alpine-minirootfs-3.11.6-x86_64.tar.gz

$ runc spec

$ sudo runc run mycont2 # `run` is a combination of `create` and `start`

/# hostname

> runc

Well, I hope you noticed, that we haven't used any image-related facilities so far. That's because we don't really need images to create and/or run containers with runc or any other OCI-compliant runtime. And just to make it clear, when I say images here I mean these layered beasts we build using Dockerfiles, push and pull from the registries like Docker Hub, and base other images on.

Reflecting on the exercise from above, we can say that runc needs just a regular filesystem directory with at least one executable file inside and a config.json. This combination is called a bundle.

The runtime doesn't know anything about the storage driver used to mount this folder, it's not even aware of its potential layered structure, thanks to union mount abstracting it away. Of course, it has nothing to do with the image building procedure and all those Dockerfile directives. The content of a bundle is also out of scope for the runtime, i.e. you can put a full Linux distro in there if you will, or keep it as lightweight as a single statically linked executable.

Any compliant container runtime should adhere to the OCI Runtime Specification and surprisingly or not the specification never mentions images! Even though the OCI Image Format specification is its sibling project. It's all about the strict separation of concerns.

Docker (or any other container engine like containerd, or podman) takes an image and converts it to an OCI bundle before invoking the lower-level container runtime like runc. I.e. it's an engine who is supposed to unpack an image, extract environment variables, exposed ports, etc. that were set on the building stage; prepare the config.json file using these details; mount filesystem layers from the image, and finally pass it over to the OCI runtime in a form of a bundle.

So, why do we need all this hassle? Wouldn't it be much simpler if we just used bundles in the first place? Apparently, this would simplify the containers' creation and starting logic. This could also positively affect the performance of the container runtime by offloading the overhead of the union mounts from the filesystem I/O.

Layered image structure combined with an overlay mount actually makes your container runtime slower.

— Ivan Velichko (@iximiuz) May 10, 2020

Why Do You Need Container Images

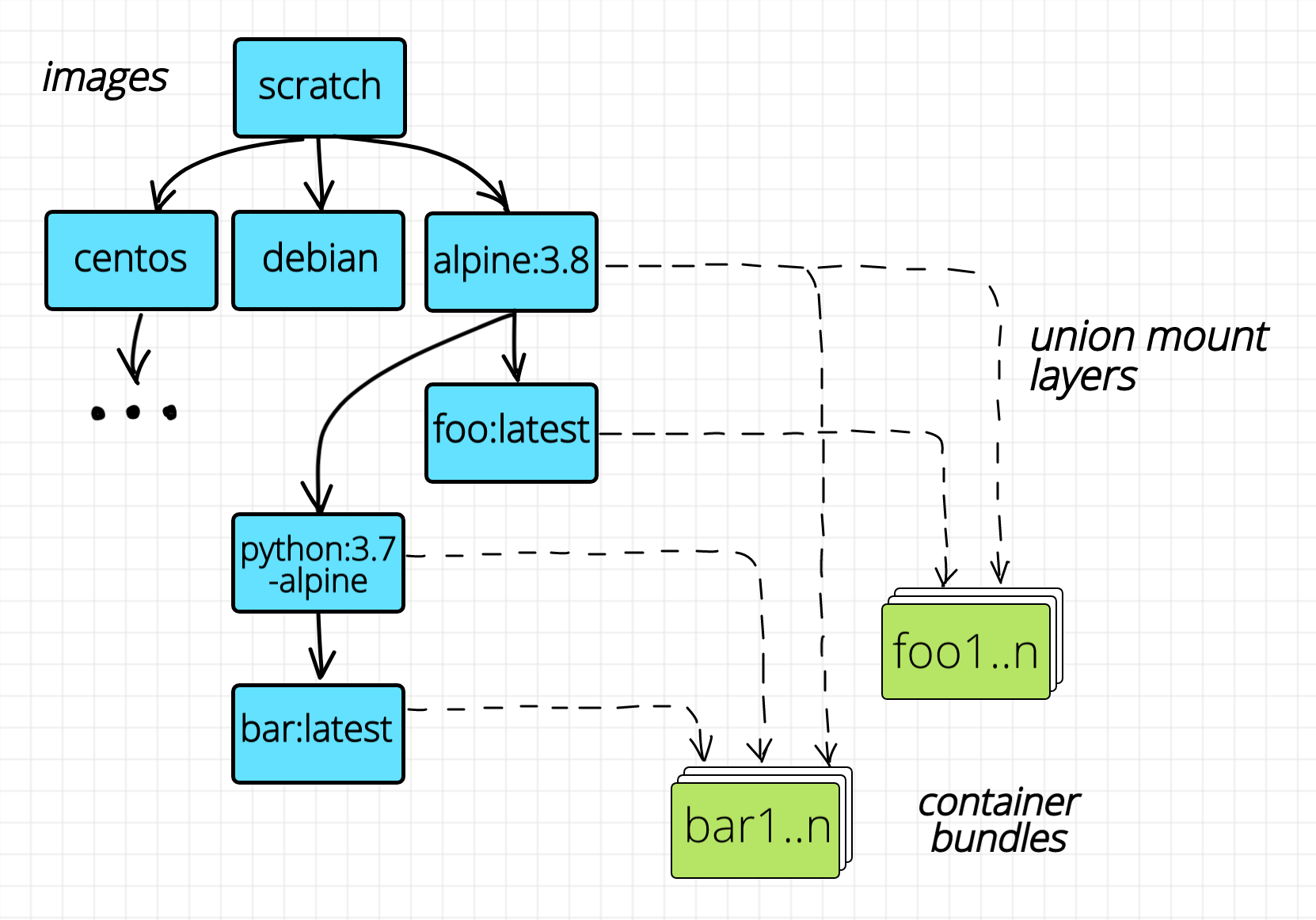

The actual reasons why we have images so widespread come from the image building and storage sides. The layered image structure and immutability of the layers are the key contributors to the extremely powerful building and storage techniques that made Docker so popular back in the days.

Imagine for a second, that we use raw bundles to store and distribute containers. In that case, if you needed to create two new custom bundles both based on the base ubuntu bundle, you'd have to copy over all the files from the ubuntu bundle into two new folders. And if you needed to create a third- or fourth-level bundles, you'd need to apply the same procedure over and over again multiplying the number of duplicate files on your disk. Moving all these files around would also add a significant build time overhead.

Of course, we need to somehow avoid this inefficiency and the layered storage seems like a great solution. If we pack the ubuntu bundle in a tar archive and compute its checksum (sha256), we will always be able to refer to it later on using content-addressable techniques. I.e. every new image derived from the base ubuntu image will be referring only the hash of the uniquely presented base image and will not include its actual content.

Images form a directed acyclic graph.

The layered image structure solves the problem of the efficient building (by eradicating the need for copying files, hence decreasing the build time) and storage (by eradicating file duplication, hence decreasing the space requirements). But what if we want to run hundreds of instances of exactly the same container on one Linux host? We may need to have hundreds of copies of the same bundle and this may occupy the full disk. Union mount to the rescue! Thanks to the immutability of the layers, we need to unpack the image only once and then mount the underlying layers as many times as we need. The only mutable layer will be the topmost (empty) layer corresponding to the bundle folder of every container.

Obviously, the pros of having images outweighed the negative impact of the layered mounts and the need for a slightly more complex container management procedures.

Wrapping up

So, the moral may have sounded something like that: while the images aren't really needed to run containers, they have made the usage of the containers simple and handy and it contributed a lot to the containers' popularity.

- Not Every Container Has an Operating System Inside

- You Don't Need an Image To Run a Container

- You Need Containers To Build Images

- Containers Aren't Linux Processes

- From Docker Container to Bootable Linux Disk Image

Don't miss new posts in the series! Subscribe to the blog updates and get deep technical write-ups on Cloud Native topics direct into your inbox.