- Computer Networking Basics For Developers

- Illustrated introduction to Linux iptables

- A Visual Guide to SSH Tunnels: Local and Remote Port Forwarding

- Bridge vs. Switch: What I Learned From a Data Center Tour

- Networking Lab: Ethernet Broadcast Domains

- Networking Lab: L3 to L2 Segments Mapping

- Networking Lab: Simple VLAN

Don't miss new posts in the series! Subscribe to the blog updates and get deep technical write-ups on Cloud Native topics direct into your inbox.

Foreword

Gee, it's my turn to throw some gloom light on iptables! There are hundreds or even thousands of articles on the topic out there, including introductory ones. I'm not going to put either formal and boring definitions here nor long lists of useful commands. I would rather try to use layman's terms and scribbling as much as possible to give you some insights about the domain before going to all these tables, rules, targets, and policies. By the way, the first time I faced this tool I was pretty much confused by the terminology too!

Probably, you already know that iptables has something to do with IP packets. Maybe even deeper - packets filtration. Or the deepest - packets modification! And maybe you've heard, that everything is happening on the kernel side, without user space code involved. For this, iptables provides a special syntax to encode different packets-affecting rules...

Linux network stack

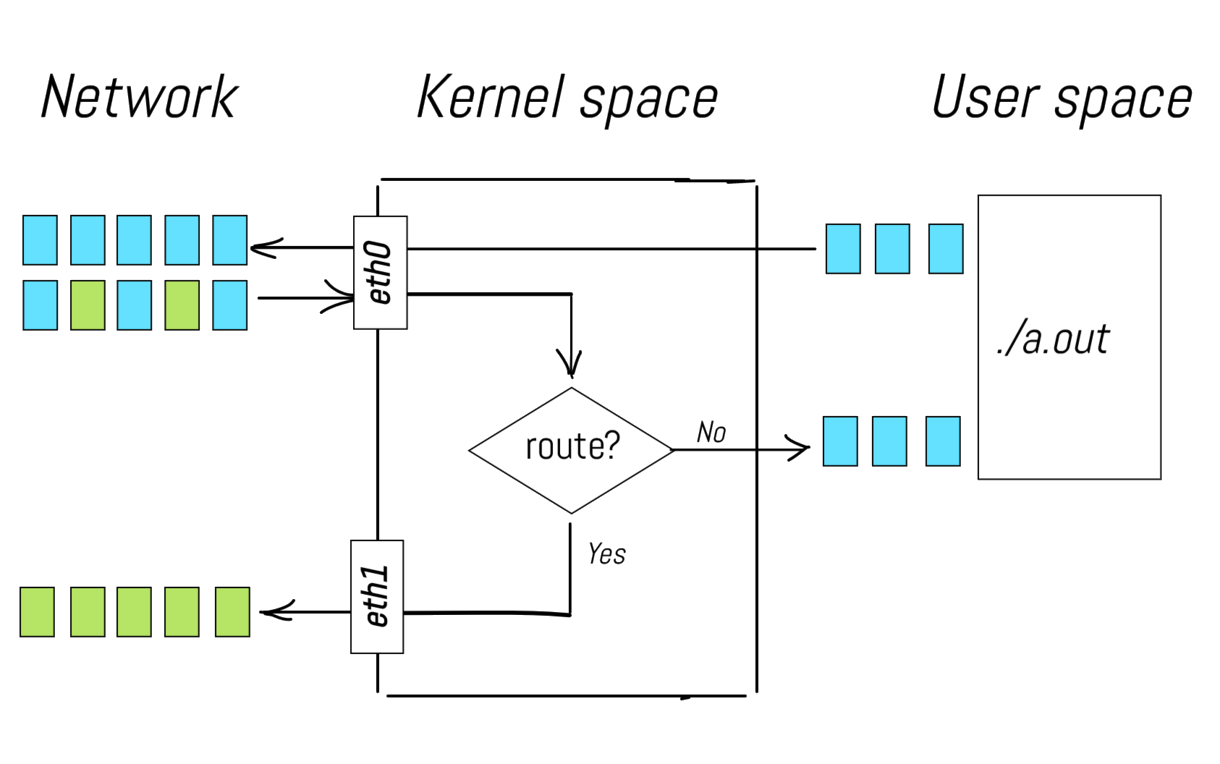

...but before trying to make an impact on a happy life of packets in the kernel space, let's try to understand their universe. When packets get created, what are their paths inside of the kernel, what are their origins and destinations, etc? Have a look at the following scenarios:

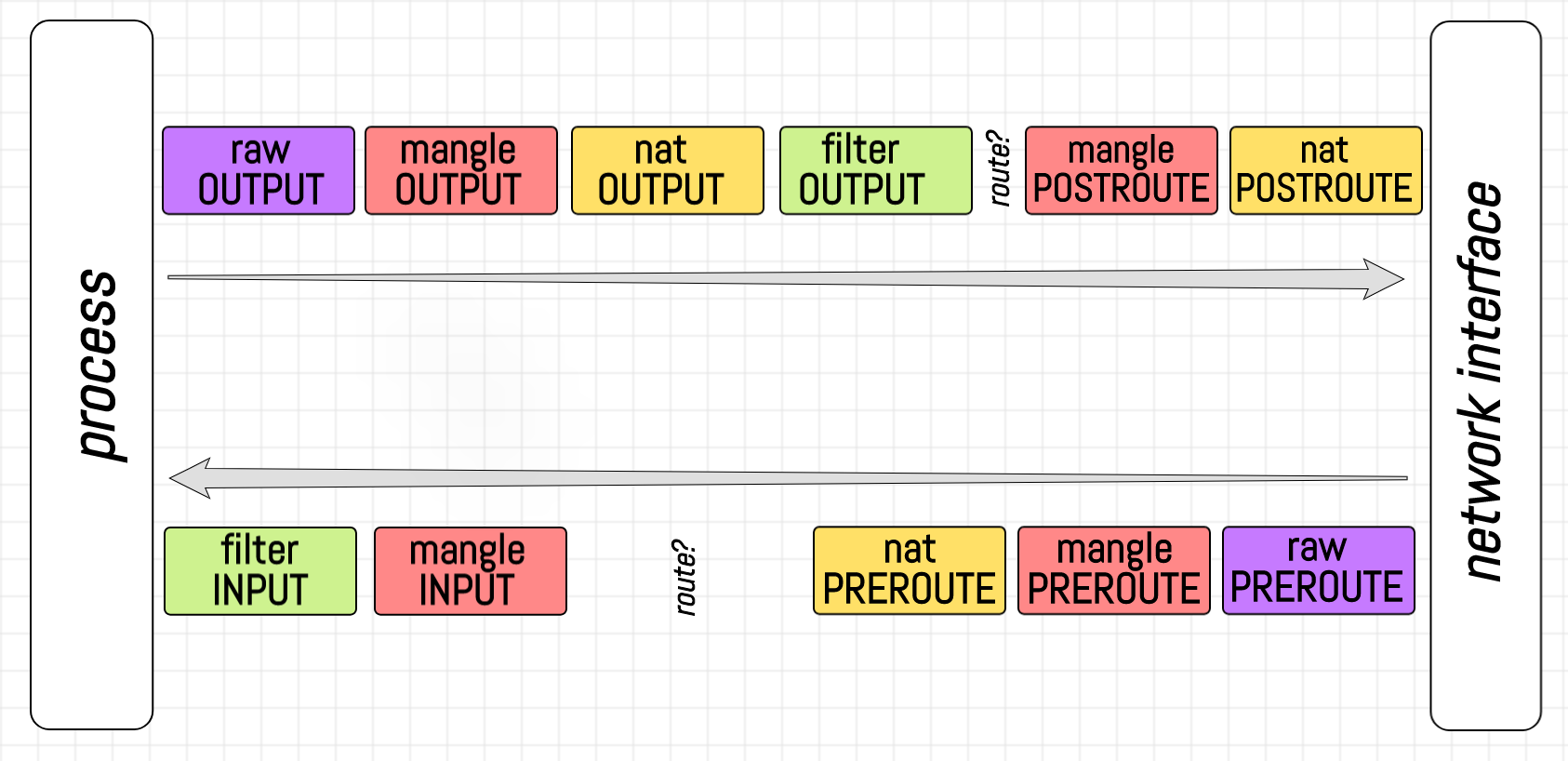

A packet arrives to the network interface, passes through the network stack and reaches a user space process.

A packet is created by a user space process, sent to the network stack, and then delivered to the network interface.

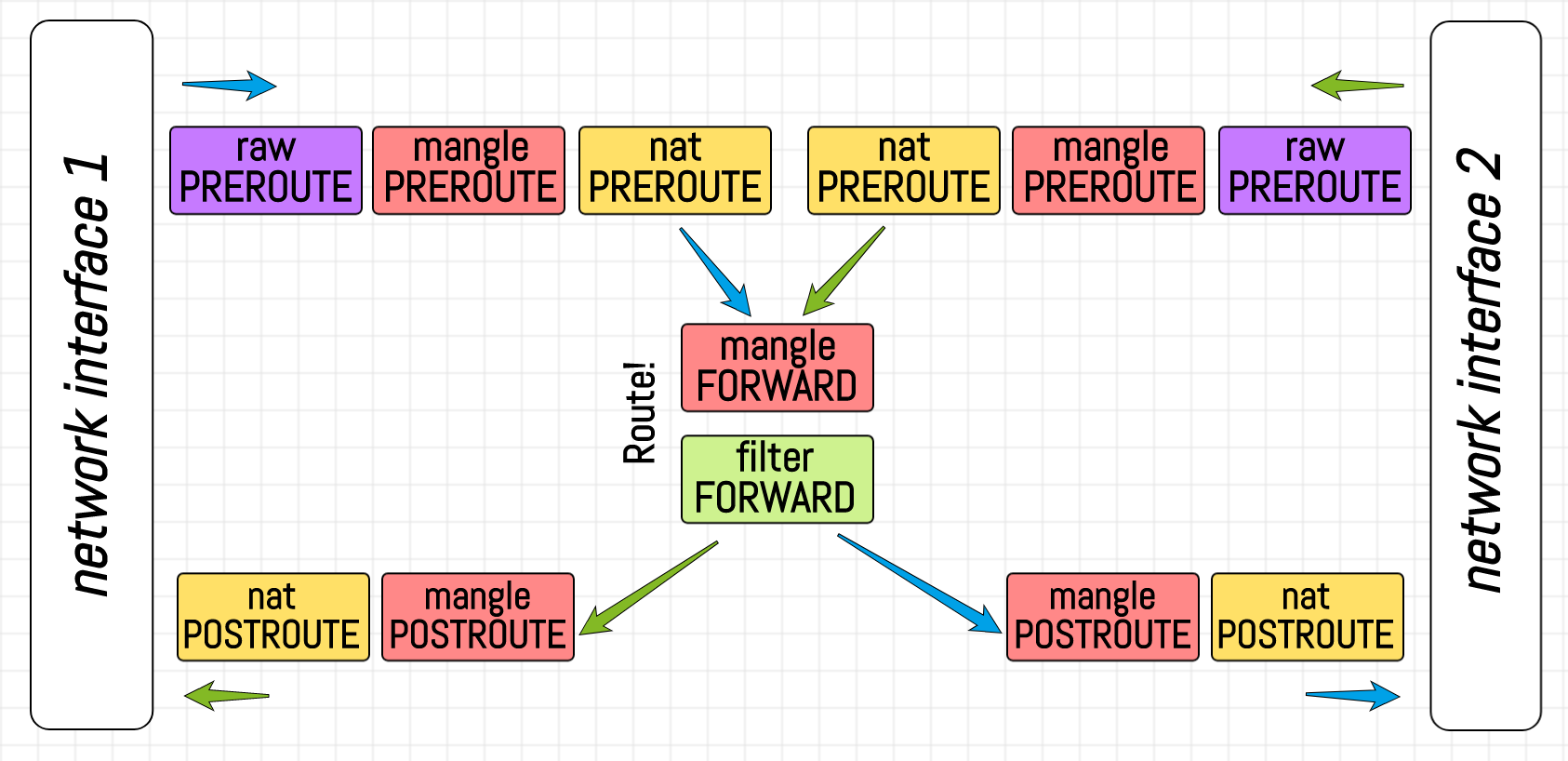

A packet arrives to the network interface and then in accordance with some routing rules is forwarded to another network interface.

What is the commonality amongst all those scenarios? Basically, all of them describe pavings of the packets' ways from a network interface through the network stack to a user space process (or another interface) and turnarounds. When I say a network stack here I just mean a bunch of layers provided by the Linux kernel to handle the network data transmission and receiving.

Routing part in the middle is provided by the built-in capability of the Linux kernel, also known as IP forwarding. Sending a non-zero value to /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_forward file activates packet forwarding between different network interfaces, effectively turning a Linux machine into a virtual router.

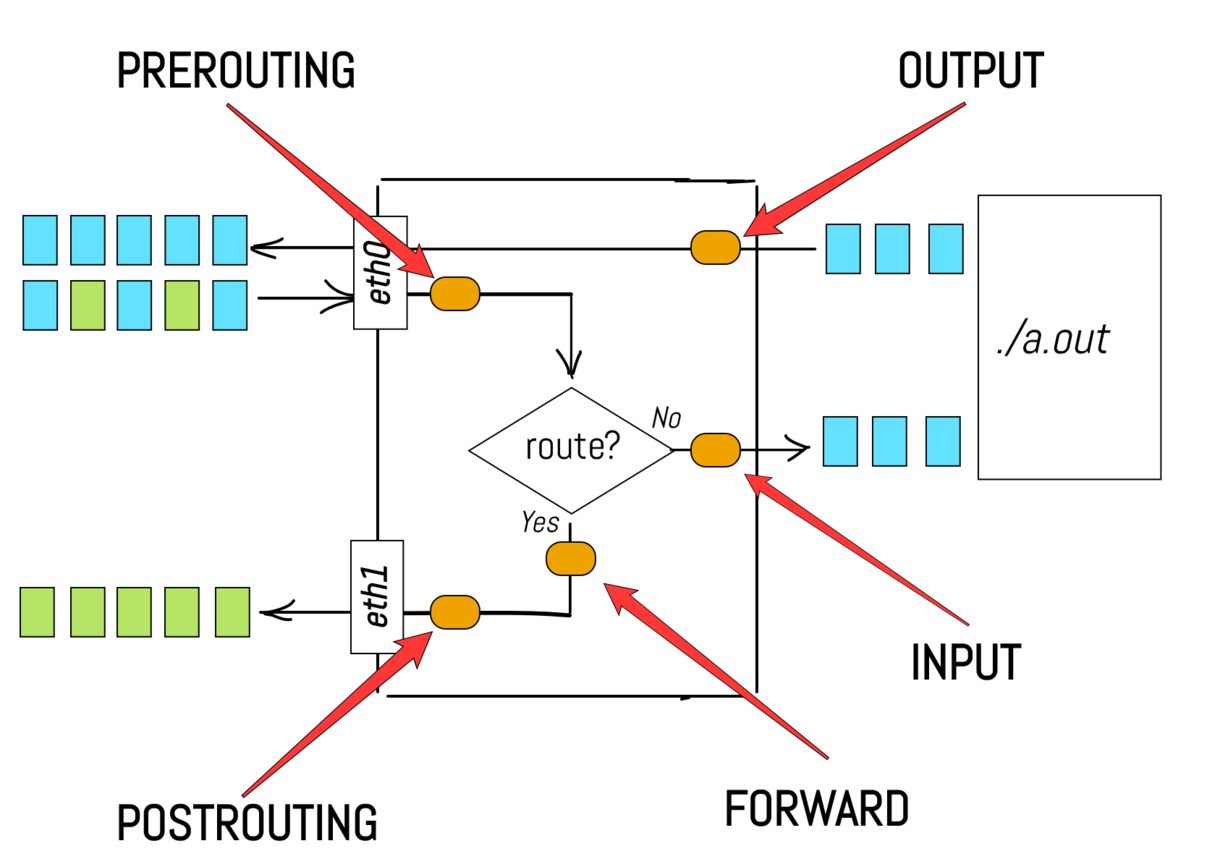

It's more or less obvious, that a properly engineered network stack should have different logical stages of the packet processing. For example, a PREROUTING stage could reside somewhere in between the packets ingestion and the actual routing procedure. Another example could be an INPUT stage, residing immediately before the user space process.

In fact, Linux network stack does provide such logical separation of stages. Now, let's get back to our primary task - packets filtration and/or alteration. What if we want to drop some packets arriving to a.out process? For example, we might dislike packets with one particular source IP address, because we suspect this IP belonging to a malicious user. Would be great to have a hook in the network stack, corresponding to the INPUT stage and allowing some extra logic to be applied to incoming packets. In our example, we might want to inject a function to check the packet's source IP address and based on this information decide whether to drop or accept the packet.

Generalizing, we need a way to register an arbitrary callback function to be executed on every incoming packet at a given stage. Luckily enough, there is a project called netfilter that provides exactly this functionality! The netfilter's code resides inside of the Linux kernel and adds all those extension points (i.e. hooks) to different stages of the network stack. It is noteworthy that iptables is just one amongst several of the user space frontend tools to configure the netfilter hooks. Even more to note here - the functionality of the netfilter is not limited by the network (i.e. IP) layer, for example, the modification of ethernet frames is also possible. However, as it follows from its name, iptables is focusing on the layers starting from the network (IP) and above.

iptables Chains Introduction

Now, let's finally try to understand the iptables terminology. You may already notice that the names we use for the stages in the network stack correspond to the iptables chains. But why on earth somebody would use the word chain for it? I don't know any anecdote behind it, but one way to explain the naming is to have a look at the usage:

# add rule "LOG every packet" to chain INPUT

$ iptables --append INPUT --jump LOG

# add rule "DROP every packet" to chain INPUT

$ iptables --append INPUT --jump DROP

In the snippet above we added multiple callbacks to the INPUT stage, and this is absolutely legitimate iptables usage. It implies though that the order of execution of the callbacks have to be defined. In reality, when a new packet arrives, the first added callback is executed first (LOG the packet), then the second callback is executed (DROP the packet). Thus, all our callbacks have been lined up in a chain! But the chain is named by the logical stage it resides. For now, let's finish with chains and switch to other parts of iptables. Later on, we will see, that there is some ambiguity in the chain abstraction.

iptables Rules, Targets, and Policies

Next, goes a rule. The rules we used in our example above are rudimentary. First, we unconditionally LOG a kernel message for every packet in the INPUT chain, then we unconditionally DROP every packet from the network stack. However, rules can be more complicated. In general, a rule specifies criteria for a packet and a target. For a sake of simplicity, let's define target now as just an action, like LOG, ACCEPT, or DROP and have a look at some examples:

# block packets with source IP 46.36.222.157

# -A is a shortcut for --append

# -j is a shortcut for --jump

$ iptables -A INPUT -s 46.36.222.157 -j DROP

# block outgoing SSH connections

$ iptables -A OUTPUT -p tcp --dport 22 -j DROP

# allow all incoming HTTP(S) connections

$ iptables -A INPUT -p tcp -m multiport --dports 80,443 \

-m conntrack --ctstate NEW,ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

$ iptables -A OUTPUT -p tcp -m multiport --dports 80,443 \

-m conntrack --ctstate ESTABLISHED -j ACCEPT

As we can see, the rule's criteria can be quite complex. We can check multiple attributes of the packet, or even some properties of the TCP connections (it implies the netfilter to be stateful, thanks to conntrack module) before deciding on the action. I'm sorry for this, but a programmer in me requires some code to be written:

def handle_packet(packet, chain):

for rule in chain:

modules = rule.modules

for m in modules:

m.ensure_loaded()

conditions = rule.conditions

if all(c.apply(packet) for c in conditions):

# terminating target, break the chain

if rule.target in ('ACCEPT', 'DROP'):

return rule.target

# TODO: handle other targets

# TODO: what shall we do if there is no single

# terminating target in the whole chain?

The idea is pretty simple. Sequentially apply all the rules in the chain until either a terminating target is encountered, or the end of the chain is reached. And here we can notice an uncovered branch in our pseudocode. We need a default action, (i.e. target) for packets managed to reach the end of the chain without being dispatched to any terminating target in the meantime. And the way to set it is called policy:

# check the default policies

$ sudo iptables --list-rules # or -S

-P INPUT ACCEPT

-P FORWARD ACCEPT

-P OUTPUT ACCEPT

# change policy for chain FORWARD to target DROP

iptables --policy FORWARD DROP # or -P

iptables Chains (continued)

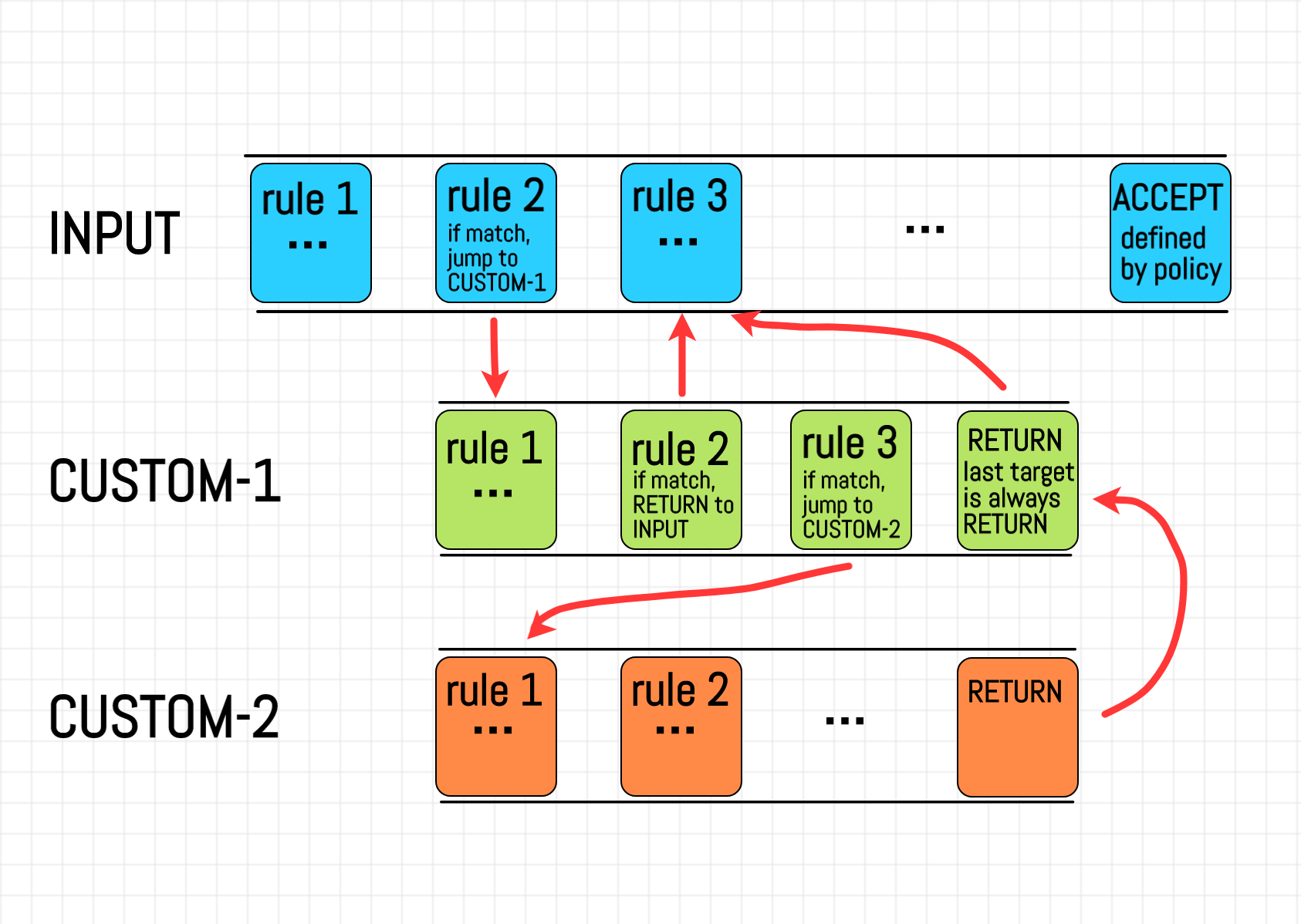

Finally, let's learn why the targets are called targets, not actions or something else. Let's look at the command we've used to set a rule iptables -A INPUT -s 46.36.222.157 -j DROP, where -j stands for --jumps. That is, as a result of the rule we can jump to a target. From man iptables:

-j, --jump target

This specifies the target of the rule; i.e., what to do

if the packet matches it. The target can be a user-defined

chain (other than the one this rule is in), one of the

special builtin targets which decide the fate of the packet

immediately, or an extension (see EXTENSIONS below).

Here it is! User-defined chains! As usually, first let's look at the example:

$ iptables -P INPUT ACCEPT

# drop all forwards by default

$ iptables -P FORWARD DROP

$ iptables -P OUTPUT ACCEPT

# create a new chain

$ iptables -N DOCKER # or --new-chain

# if outgoing interface is docker0, jump to DOCKER chain

$ iptables -A FORWARD -o docker0 -j DOCKER

# add some specific to Docker rules to the user-defined chain

$ iptables -A DOCKER ...

$ iptables -A DOCKER ...

$ iptables -A DOCKER ...

# jump back to the caller (i.e. FORWARD) chain

$ iptables -A DOCKER -j RETURN

But how come? As we saw above, chains have had a one-to-one correspondence to the predefined logical stages of the network stack. Does the fact that users can define their own chains mean we can introduce new stages to the kernel's handling pipeline? I hardly think so. I might be totally wrong here, but to me, it seems like a violation of the Single responsibility principle. A chain seems to be a good abstraction for a named sequence of rules. There is some similarity between chains and named subroutines (aka functions, aka procedures) in traditional programming languages. Ability to jump from an arbitrary place in one chain to the beginning of another chain and then RETURN to the caller chain makes the similarity even stronger. However, PREROUTING, INPUT, FORWARD, OUTPUT, and POSTROUTING chains have a special meaning and cannot be overwritten. I can see some similarity to the main() function in some programming languages having a special purpose, but this double-ended nature of chains made the learning curve of iptables pretty steep to me.

To summarise, a user-defined chain is a special kind of target, used as a named sequence of rules. The capabilities of user-defined chains are rather limited. For example, a user-defined chain can't have a policy. From man iptables:

-P, --policy chain target

Set the policy for the chain to the given target.

See the section TARGETS for the legal targets.

Only built-in (non-user-defined) chains can have policies,

and neither built-in nor user-defined chains can be policy

targets.

Obviously, the code snippet above should be significantly rewritten to incorporate handling of user-defined chains.

iptables Tables introduction

Well, we are almost there! We've covered chains, rules, and policies. Now it's finally time to learn about tables. After all, the tool is called iptables.

Actually, in all the examples above we implicitly used a table called filter. I'm not sure about the official definition of a table, but I always refer to a table as a logical grouping and isolation of chains. As we already know, there is a table for chains that manage packets filtration. However, if we want to modify some packets, there is another table, called mangle. It's absolutely valid desire to be able to filter packets on the FORWARD stage. However, it's also fine to modify packets on that stage. Hence, both filter and mangle tables will have FORWARD chains. However, those chains are completely independent.

The number of supported tables can vary between different versions of the kernel, but the most prominent tables are usually there:

filter:

This is the default table (if no -t option is passed). It contains

the built-in chains INPUT (for packets destined to local sockets),

FORWARD (for packets being routed through the box), and OUTPUT

(for locally-generated packets). nat:

This table is consulted when a packet that creates a new connection is encountered.

It consists of three built-ins: PREROUTING (for altering packets as soon as

they come in), OUTPUT (for altering locally-generated packets before routing),

and POSTROUTING (for altering packets as they are about to go out). IPv6 NAT support

is available since kernel 3.7. mangle:

This table is used for specialized packet alteration. Until kernel 2.4.17 it had two

built-in chains: PREROUTING (for altering incoming packets before routing)

and OUTPUT (for altering locally-generated packets before routing). Since kernel 2.4.18,

three other built-in chains are also supported: INPUT (for packets coming into the box

itself), FORWARD (for altering packets being routed through the box), and POSTROUTING

(for altering packets as they are about to go out). raw:

This table is used mainly for configuring exemptions from connection tracking in

combination with the NOTRACK target. It registers at the netfilter hooks with

higher priority and is thus called before ip_conntrack, or any other IP tables.

It provides the following built-in chains: PREROUTING (for packets arriving via

any network interface) OUTPUT (for packets generated by local processes) security:

This table is used for Mandatory Access Control (MAC) networking rules, such as those

enabled by the SECMARK and CONNSECMARK targets. Mandatory Access Control is implemented

by Linux Security Modules such as SELinux. The security table is called after the filter

table, allowing any Discretionary Access Control (DAC) rules in the filter table to take

effect before MAC rules. This table provides the following built-in chains: INPUT (for

packets coming into the box itself), OUTPUT (for altering locally-generated packets before

routing), and FORWARD (for altering packets being routed through the box).What is really interesting here is the collision of chains between tables. What will happen to a packet if filter.INPUT chain has a DROP target but mangle.INPUT chain has an ACCEPT target, both within the affirmative rules? Which chain has higher precedence? Let's try to check it out!

For this, we need to add LOG targets to all the chains of all the tables and conduct the following experiment:

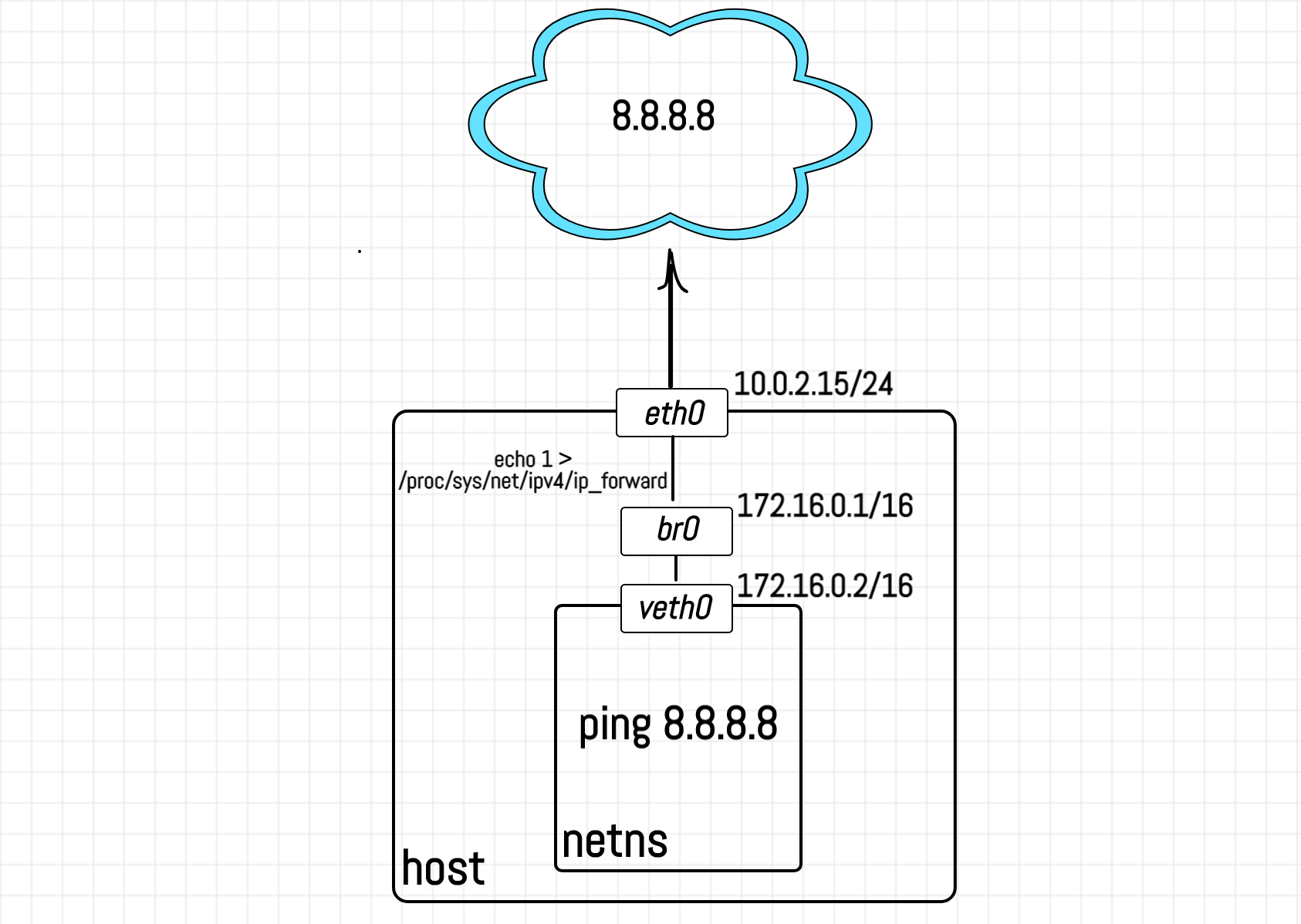

Click here to learn how to set up the environment.

We need logs for both the client and the router network stacks on the same stream to have a comprehensive overview of the relations between tables and chains. For this we are going to simulate 2 machines on a single Linux host by using network namespaces feature. The main part of the experiment is LOGging of IP packets. For a long time, LOG target was disabled for the non-root namespaces to prevent potential host's denials of service from the isolated processes. Luckily, starting from Linux kernel 4.11 there is a way to enable netfilter logs for namespaces via sending a non-zero value to /proc/sys/net/netfilter/nf_log_all_netns. But don't do this on production!

First, let's create a network namespace:

# run on host:

$ unshare -r --net bash

# namespace (same terminal session):

$ echo $$

2979 # remember this PID

In the second terminal, we need to configure the host:

# run on host:

$ sudo -i

# create a veth interface

$ ip link add vGUEST type veth peer name vHOST

# move one of its peers to network namespace

$ ip link set vGUEST netns 2979 # PID from above

# create linux bridge

$ ip link add br0 type bridge

# wire vHOST to br0

$ ip link set vHOST master br0

# set IP addresses and bring devices up

$ ip addr add 172.16.0.1/16 dev br0

$ ip link set br0 up

$ ip link set vHOST up

$ ip addr

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 ::1/128 scope host

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

2: eth0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether 52:54:00:26:10:60 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 10.0.2.15/24 brd 10.0.2.255 scope global noprefixroute dynamic eth0

valid_lft 85752sec preferred_lft 85752sec

inet6 fe80::5054:ff:fe26:1060/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

3: vHOST@if4: <NO-CARRIER,BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue master br0 state LOWERLAYERDOWN group default qlen 1000

link/ether c2:96:cf:97:f4:12 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 0

5: br0: <NO-CARRIER,BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state DOWN group default qlen 1000

link/ether c2:96:cf:97:f4:12 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 172.16.0.1/16 scope global br0

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

# turn the host into a virtual router

iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -o eth0 -j MASQUERADE

$ echo 1 > /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_forward

# and don't forget to enable netfilter logs in namespaces

$ echo 1 > /proc/sys/net/netfilter/nf_log_all_netns

Now finish the network interface setup on the namespace side:

# run in network namespace:

# bring devices up

$ ip link set lo up

$ ip link set vGUEST up

# configure IP address

$ ip addr add 172.16.0.2/16 dev vGUEST

$ ip addr

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 ::1/128 scope host

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

4: vGUEST@if3: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc noqueue state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether c2:31:a8:8b:d7:f8 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 0

inet 172.16.0.2/16 scope global vGUEST

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 fe80::c031:a8ff:fe8b:d7f8/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

# set default route via br0

$ ip route add default via 172.16.0.1

$ ip route

default via 172.16.0.1 dev vGUEST

172.16.0.0/16 dev vGUEST proto kernel scope link src 172.16.0.2

Check out and update iptables rules in the namespace:

# run in network namespace:

$ iptables -S -t filter

-P INPUT ACCEPT

-P FORWARD ACCEPT

-P OUTPUT ACCEPT

$ iptables -S -t nat

-P PREROUTING ACCEPT

-P INPUT ACCEPT

-P OUTPUT ACCEPT

-P POSTROUTING ACCEPT

$ iptables -S -t mangle

-P PREROUTING ACCEPT

-P INPUT ACCEPT

-P FORWARD ACCEPT

-P OUTPUT ACCEPT

-P POSTROUTING ACCEPT

$ iptables -S -t raw

-P PREROUTING ACCEPT

-P OUTPUT ACCEPT

$ iptables -t filter -A INPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_FILTER_INPUT "

$ iptables -t filter -A FORWARD -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_FILTER_FORWARD "

$ iptables -t filter -A OUTPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_FILTER_OUTPUT "

$ iptables -t nat -A PREROUTING -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_NAT_PREROUTE "

$ iptables -t nat -A INPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_NAT_INPUT "

$ iptables -t nat -A OUTPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_NAT_OUTPUT "

$ iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_NAT_POSTROUTE "

$ iptables -t mangle -A PREROUTING -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_MANGLE_PREROUTE "

$ iptables -t mangle -A INPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_MANGLE_INPUT "

$ iptables -t mangle -A FORWARD -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_MANGLE_FORWARD "

$ iptables -t mangle -A OUTPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_MANGLE_OUTPUT "

$ iptables -t mangle -A POSTROUTING -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_MANGLE_POSTROUTE "

$ iptables -t raw -A PREROUTING -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_RAW_PREROUTE "

$ iptables -t raw -A OUTPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "NETNS_RAW_OUTPUT "

Notice that iptables rules on the host aren't affected by the settings from the namespace:

# run on host:

$ iptables -S -t filter

-P INPUT ACCEPT

-P FORWARD ACCEPT

-P OUTPUT ACCEPT

$ iptables -S -t nat

-P PREROUTING ACCEPT

-P INPUT ACCEPT

-P OUTPUT ACCEPT

-P POSTROUTING ACCEPT

-A POSTROUTING -o eth0 -j MASQUERADE

$ iptables -S -t mangle

-P PREROUTING ACCEPT

-P INPUT ACCEPT

-P FORWARD ACCEPT

-P OUTPUT ACCEPT

-P POSTROUTING ACCEPT

$ iptables -S -t raw

-P PREROUTING ACCEPT

-P OUTPUT ACCEPT

Update iptables rules on the host:

# run on host:

$ iptables -t filter -A INPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_FILTER_INPUT "

$ iptables -t filter -A FORWARD -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_FILTER_FORWARD "

$ iptables -t filter -A OUTPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_FILTER_OUTPUT "

$ iptables -t nat -A PREROUTING -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_NAT_PREROUTE "

$ iptables -t nat -A INPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_NAT_INPUT "

$ iptables -t nat -A OUTPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_NAT_OUTPUT "

$ iptables -t nat -A POSTROUTING -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_NAT_POSTROUTE "

$ iptables -t mangle -A PREROUTING -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_MANGLE_PREROUTE "

$ iptables -t mangle -A INPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_MANGLE_INPUT "

$ iptables -t mangle -A FORWARD -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_MANGLE_FORWARD "

$ iptables -t mangle -A OUTPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_MANGLE_OUTPUT "

$ iptables -t mangle -A POSTROUTING -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_MANGLE_POSTROUTE "

$ iptables -t raw -A PREROUTING -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_RAW_PREROUTE "

$ iptables -t raw -A OUTPUT -j LOG --log-prefix "HOST_RAW_OUTPUT "

And finally ping 8.8.8.8 from the namespace while tailf-ing kernel messages on the host:

# run in network namespace:

$ ping 8.8.8.8

# run on host:

$ tail -f /var/log/messages

Now if we start pinging an external address, like 8.8.8.8, we can notice an interesting pattern arising in the netfilter logs:

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: NETNS_RAW_OUTPUT IN= OUT=vGUEST SRC=172.16.0.2 DST=8.8.8.8 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=64 ID=2089 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=8 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: NETNS_MANGLE_OUTPUT IN= OUT=vGUEST SRC=172.16.0.2 DST=8.8.8.8 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=64 ID=2089 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=8 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: NETNS_FILTER_OUTPUT IN= OUT=vGUEST SRC=172.16.0.2 DST=8.8.8.8 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=64 ID=2089 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=8 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: NETNS_MANGLE_POSTROUTE IN= OUT=vGUEST SRC=172.16.0.2 DST=8.8.8.8 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=64 ID=2089 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=8 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: HOST_RAW_PREROUTE IN=br0 OUT= MAC=c2:96:cf:97:f4:12:c2:31:a8:8b:d7:f8:08:00 SRC=172.16.0.2 DST=8.8.8.8 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=64 ID=2089 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=8 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: HOST_MANGLE_PREROUTE IN=br0 OUT= MAC=c2:96:cf:97:f4:12:c2:31:a8:8b:d7:f8:08:00 SRC=172.16.0.2 DST=8.8.8.8 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=64 ID=2089 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=8 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: HOST_MANGLE_FORWARD IN=br0 OUT=eth0 MAC=c2:96:cf:97:f4:12:c2:31:a8:8b:d7:f8:08:00 SRC=172.16.0.2 DST=8.8.8.8 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=63 ID=2089 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=8 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: HOST_FILTER_FORWARD IN=br0 OUT=eth0 MAC=c2:96:cf:97:f4:12:c2:31:a8:8b:d7:f8:08:00 SRC=172.16.0.2 DST=8.8.8.8 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=63 ID=2089 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=8 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: HOST_MANGLE_POSTROUTE IN= OUT=eth0 SRC=172.16.0.2 DST=8.8.8.8 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=63 ID=2089 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=8 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: HOST_RAW_PREROUTE IN=eth0 OUT= MAC=52:54:00:26:10:60:52:54:00:12:35:02:08:00 SRC=8.8.8.8 DST=10.0.2.15 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=62 ID=17376 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=0 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: HOST_MANGLE_PREROUTE IN=eth0 OUT= MAC=52:54:00:26:10:60:52:54:00:12:35:02:08:00 SRC=8.8.8.8 DST=10.0.2.15 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=62 ID=17376 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=0 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: HOST_MANGLE_FORWARD IN=eth0 OUT=br0 MAC=52:54:00:26:10:60:52:54:00:12:35:02:08:00 SRC=8.8.8.8 DST=172.16.0.2 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=61 ID=17376 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=0 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: HOST_FILTER_FORWARD IN=eth0 OUT=br0 MAC=52:54:00:26:10:60:52:54:00:12:35:02:08:00 SRC=8.8.8.8 DST=172.16.0.2 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=61 ID=17376 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=0 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: HOST_MANGLE_POSTROUTE IN= OUT=br0 SRC=8.8.8.8 DST=172.16.0.2 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=61 ID=17376 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=0 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: NETNS_RAW_PREROUTE IN=vGUEST OUT= MAC=c2:31:a8:8b:d7:f8:c2:96:cf:97:f4:12:08:00 SRC=8.8.8.8 DST=172.16.0.2 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=61 ID=17376 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=0 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: NETNS_MANGLE_PREROUTE IN=vGUEST OUT= MAC=c2:31:a8:8b:d7:f8:c2:96:cf:97:f4:12:08:00 SRC=8.8.8.8 DST=172.16.0.2 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=61 ID=17376 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=0 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: NETNS_MANGLE_INPUT IN=vGUEST OUT= MAC=c2:31:a8:8b:d7:f8:c2:96:cf:97:f4:12:08:00 SRC=8.8.8.8 DST=172.16.0.2 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=61 ID=17376 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=0 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

Jun 21 13:25:19 localhost kernel: NETNS_FILTER_INPUT IN=vGUEST OUT= MAC=c2:31:a8:8b:d7:f8:c2:96:cf:97:f4:12:08:00 SRC=8.8.8.8 DST=172.16.0.2 LEN=84 TOS=0x00 PREC=0x00 TTL=61 ID=17376 DF PROTO=ICMP TYPE=0 CODE=0 ID=3197 SEQ=34

The logs are pretty verbose, but try to focus on the log prefixes only. The pattern is as follows:

NETNS_RAW_OUTPUT

NETNS_MANGLE_OUTPUT

NETNS_FILTER_OUTPUT

NETNS_MANGLE_POSTROUTE

HOST_RAW_PREROUTE

HOST_MANGLE_PREROUTE

HOST_MANGLE_FORWARD

HOST_FILTER_FORWARD

HOST_MANGLE_POSTROUTE

HOST_RAW_PREROUTE

HOST_MANGLE_PREROUTE

HOST_MANGLE_FORWARD

HOST_FILTER_FORWARD

HOST_MANGLE_POSTROUTE

NETNS_RAW_PREROUTE

NETNS_MANGLE_PREROUTE

NETNS_MANGLE_INPUT

NETNS_FILTER_INPUT

From this, we can get a rough idea about the chains precedence. Note that while the namespace in our example behaves like a normal client machine sending requests to the Internet through its default route, the host serves a router's role:

Chains precedence on client.

Chains precedence on router.

Conclusion

It might look like iptables is an ancient technology. Does it make sense to spend your time learning it? But have a look at Docker or Kubernetes - booming bleeding edge products. Both heavily utilize iptables under the hood to set up and manage their networking layers! Don't be fooled, without learning fundamental things like netfilter, iptables, IPVS it will be never possible neither develop nor operate modern cluster management tools on a serious scale.

- Computer Networking Basics For Developers

- Illustrated introduction to Linux iptables

- A Visual Guide to SSH Tunnels: Local and Remote Port Forwarding

- Bridge vs. Switch: What I Learned From a Data Center Tour

- Networking Lab: Ethernet Broadcast Domains

- Networking Lab: L3 to L2 Segments Mapping

- Networking Lab: Simple VLAN

Don't miss new posts in the series! Subscribe to the blog updates and get deep technical write-ups on Cloud Native topics direct into your inbox.