I want to share my very recent experience with agentic coding. Primarily because I was (finally) genuinely impressed by the productivity gains it unlocked. But also because I'm fed up with posts on X claiming that you can now build absolutely anything in no time, with almost no prior domain knowledge or programming experience. While that might be true to some extent for prototyping or throwaway apps you can one-shot, this is not what I'm seeing in real production systems.

The amount of engineering effort, domain knowledge in general, and familiarity with a project's codebase in particular now likely matter more than ever. Agents generate code extremely fast, and that can be both a blessing and a curse for long-term maintainability and extensibility.

Level up your server-side game — join 20,000 engineers getting insightful learning materials straight to their inbox.

My background and the gunia pig project

I've been coding professionally for more than 15 years - across all sorts of projects, from frontend to backend to infra and systems programming. I've worked in all kinds of settings: smaller and larger startups, big(ish) tech, open source, and more recently my own bootstrapped software company, iximiuz Labs. The latter will be the main source of case studies for this post.

Over the past month, I produced (at least) 50K lines of code (LOC) overhauling and extending the iximiuz Labs backend and frontend. None of this code is slop, and most of the features I shipped were non-trivial. All changes and additions were made to an existing mid-sized production codebase: three years in development and ~100K LOC when my coding spree started (now around 150K LOC). The absolute majority of the code added last month was AI-generated.

I couldn't dream of this level of productivity not only back in 2023, when iximiuz Labs was founded, but even in mid-2025 - and I've been using AI for writing code since the "hey, look, Copilot guessed this line correctly" days.

For most of 2025, my primary agent was Cursor (with assorted models), mainly because I still use an IDE to browse and adjust generated code, and it was convenient to command agents and make tweaks from the same window. But I kept trying Claude Code, and gradually it started noticeably outperforming Cursor's agent. That made Claude Code my primary agent as of around October 2025.

I quickly switched to the $200/month plan because I kept running into the limits of the $20/month plan. Most of the time, I run just one foreground agent, because:

- I work on an existing codebase where all changes need to be proofread - for both sanity and consistency with existing architectural and style requirements.

- Either I'm not smart enough or my problems are advanced enough, but I can't fit more than one problem at a time in my own head.

- The iximiuz Labs development environment is fairly involved, and I can't afford - money- and time-wise - to set up multiple copies. Two (or more) agents working against the same environment conflict badly.

- Running agents against a "bare" codebase (without a dev environment) removes about 90% of their usefulness. Agents need to run tests and verify changes, and many of iximiuz Labs' tests are integration or end-to-end tests. Verification often requires a browser - which is not a problem with Chrome DevTools MCP - but I can still run only one copy of the dev server, and thus one web app.

Sometimes I fire up a second agent - on the same codebase or another project - but only for small changes, like cosmetic refactorings or fixing tests I'm already very familiar with.

Case studies (kinda sorta)

Below is a non-exhaustive list of observations reflecting the strengths and weaknesses of coding agents when applied to a real-world production codebase. I'm calling them "case studies," but unlike typical case studies (which are usually full of bullshit), these are based on much smaller and far more concrete examples that most developers should be able to relate to.

Simple infra feature: Google Cloud Storage client

Let's open with an example of a simple infrastructural feature that turned out to be surprisingly hard to ship for both Claude Code (Opus 4.5) and Codex CLI (GPT-5.1-Codex).

iximiuz Labs relies on an S3-compatible storage to persist snapshots of VM volumes between playground runs. The code uses the standard AWS SDK for Go to generate pre-signed URLs to download and upload (multi-part) volume snapshots as S3 objects. The following SDK methods are used:

PresignGetObject()CreateMultipartUpload()PresignUploadPart()CompleteMultipartUpload()

A small extra complication comes from the use of server-side encryption with customer-provided keys (SSE-C). SSE-C allows each volume to be encrypted with a custom key (instead of relying on S3's default encryption at rest), and these keys can potentially be provided by the end user [of iximiuz Labs]. Technically, this means all of the above methods must accept three extra options, which translate into the following HTTP headers in S3 API calls:

x-amz-server-side-encryption-customer-algorithm(alwaysAES256)x-amz-server-side-encryption-customer-key(the actual encryption key)x-amz-server-side-encryption-customer-key-MD5(the MD5 checksum of the key)

Amazon's own S3 can get pretty expensive due to egress charges, and since iximiuz Labs' worker nodes don't run in AWS, I decided to use Cloudflare R2 instead (which has free egress). Luckily, the R2 API is fully compatible with the S3 API for the parts I needed, so I only had to replace the endpoint and API keys in the AWS SDK client initialization.

Then a requirement to support Google Cloud Storage (GCS) came up. Volume storage is a very sensitive part of iximiuz Labs, so it's covered with extensive integration tests, and I could simply point the agent to the test suite to verify readiness. My initial assumption was that the problem would be as simple as replacing the API endpoint and access keys once again, so I tasked Claude Code with it.

To my utter surprise, after juggling the code for about 30 minutes, Claude Code admitted defeat. It turned out that Cloud Storage's S3 compatibility is less complete than R2's. GCS offers an S3 compatibility layer via its XML API, but - in classic Google fashion - they've (supposedly) hardened the authentication part, so the latest AWS SDK (v2) doesn't work with the GCS XML API out of the box.

Claude Code attempted to downgrade the SDK (without asking me - I wouldn't have approved it anyway). That might even have worked, but the SSE-C part ruined everything: Google expects different header names (x-goog-encryption-algorithm instead of x-amz-server-side-encryption-customer-algorithm, x-goog-encryption-key instead of x-amz-server-side-encryption-customer-key, etc.), and the AWS SDK for Go doesn't expose a way to change them. So Claude Code decided the requirements were impossible to fulfill - a rather rare outcome.

After wrapping my head around these findings, I asked Claude Code to replace the AWS SDK client usage with a project-specific client exposing only the four methods above, make it an interface, and create two implementations: an AWS SDK-based one for R2, and a custom one using the GCS XML API. A perfect refactoring followed almost instantly - but after another 30 minutes, Claude Code again failed to produce a working GCS client. This time it couldn't figure out how to sign XML API requests using HMAC-SHA256.

That surprised me, but since I had no prior experience with either GCS or manually sending requests to an S3-compatible API, I couldn't easily verify Claude Code's claim that the requested functionality was impossible.

I turned to ChatGPT, which confirmed the infeasibility of SSE-C support on GCS - even though I was very careful not to hint at that outcome. I also tried Codex CLI, which failed in the same way as Claude Code: on implementing request-signature logic.

The next day, I gave up on adding SSE-C support for GCS and asked Claude Code to generate a simpler GCS client that still used the S3-compatible XML API but omitted SSE-C headers. Claude Code quickly produced something that made most acceptance tests pass (except the SSE-C-specific ones).

But my gut still told me that SSE-C must be supported on GCS. So I tried one last wild attempt: I asked Claude Code to add SSE-C support to the working client it had just generated. And it did - requiring only a few minor changes.

Why this rant? I wanted to use it as an example of a surprising agent failure. Traditionally, the better your problem is defined, the smaller the scope, and the easier the verification, the higher the autonomy and success rate you should expect from the agent. But clearly, there are exceptions. This problem was extremely well defined and perfectly verifiable via comprehensive, fast acceptance tests - yet both Claude Code and Codex CLI confidently failed after hours of autonomous work, while ChatGPT simply gaslit me.

If I'd had prior experience with GCP and/or the S3 XML API, I could have shipped this feature end-to-end in under an hour, using a coding agent as a dumb refactoring and code-generation tool. That's how long my second attempt took. Instead, it cost me a full day of running agents, reviewing nonsense output, and reading ChatGPT replies and GCP docs to gain the required context.

Most importantly, writing this S3 API client manually would probably have taken me a full week. Even though the code itself is straightforward, figuring out all the nuances of signature generation by hand is always extremely time-consuming. I've left the result as a gist in case someone else needs it in the future.

Typical full-stack feature: a simple author profile page

From the very beginning, iximiuz Labs didn't have an internal author profile page. Authors were expected to link to an external profile (LinkedIn, GitHub, a personal website, etc.). But I always wanted to add a proper internal profile - something not too complicated, but nice-looking. With recent improvements in Claude Code, it felt like I could ship such a page in just a few hours.

It did indeed take just a couple of prompts and maybe 30 minutes to generate and polish the public autor profile page. But behind it sits an internal author dashboard that allows editing author details - and that part was much harder to build, even though it was "just CRUD" on paper.

Initially, I gave Claude Code a comprehensive description of what needed to happen from the end user's (author's) perspective. Think of it as a good product-owner-style request: concrete requirements about structure, behavior, and editing capabilities, with no implementation assumptions. The implementation that followed, however, was dangerously flawed.

The single externalProfileUrl field of the Author model was replaced with a socialProfileUrls dictionary (good), but Claude Code missed about 20% of usages (okay-ish), and introduced a hacky DB field _socialProfileUrls (bad - schema changes are always the most painful to revert).

The idea was to expose a virtual socialProfileUrls field that converted the old externalProfileUrl to the new format if _socialProfileUrls was empty (clever). But the implementation wasn't idiomatic for my ORM (mongoose). A custom getter on the existing field could have achieved the same thing without the confusing socialProfileUrls / _socialProfileUrls split - which, incidentally, Claude Code (or its successor) would likely trip over first.

On top of that, Claude Code introduced an XSS vulnerability by not validating javascript: and similar URLs when rendering social profile links.

And that was just one of a dozen issues I found during review. Another critical problem was the lack of an author nickname uniqueness check, which I explicitly required. Claude Code failed to create a unique index on the new name field because existing DB records had empty names that would break the migration. Instead of fixing this, it silently skipped the relevant tests and claimed success.

After reviewing ~2,000 LOC of technically working but deeply flawed code, I tested another hypothesis. Instead of addressing issues one by one, I wrote a comprehensive prompt describing all findings and required fixes (around 500–750 words) and sent Claude Code on another autonomous run. And wow - it did terribly. Almost none of the issues were properly fixed. Some were half-mitigated, others ignored entirely.

I ended up reverting the change and tackling each issue individually, explicitly telling Claude Code what to do. This time, it performed great.

The simple public author profile and internal dashboard together took two full working days and a lot of focus to ship. That's not even close to autonomous coding - but it was still a huge time saver. Doing the same feature by hand would have taken me at least a week.

Typical frontend feature: dashboard pane redesign

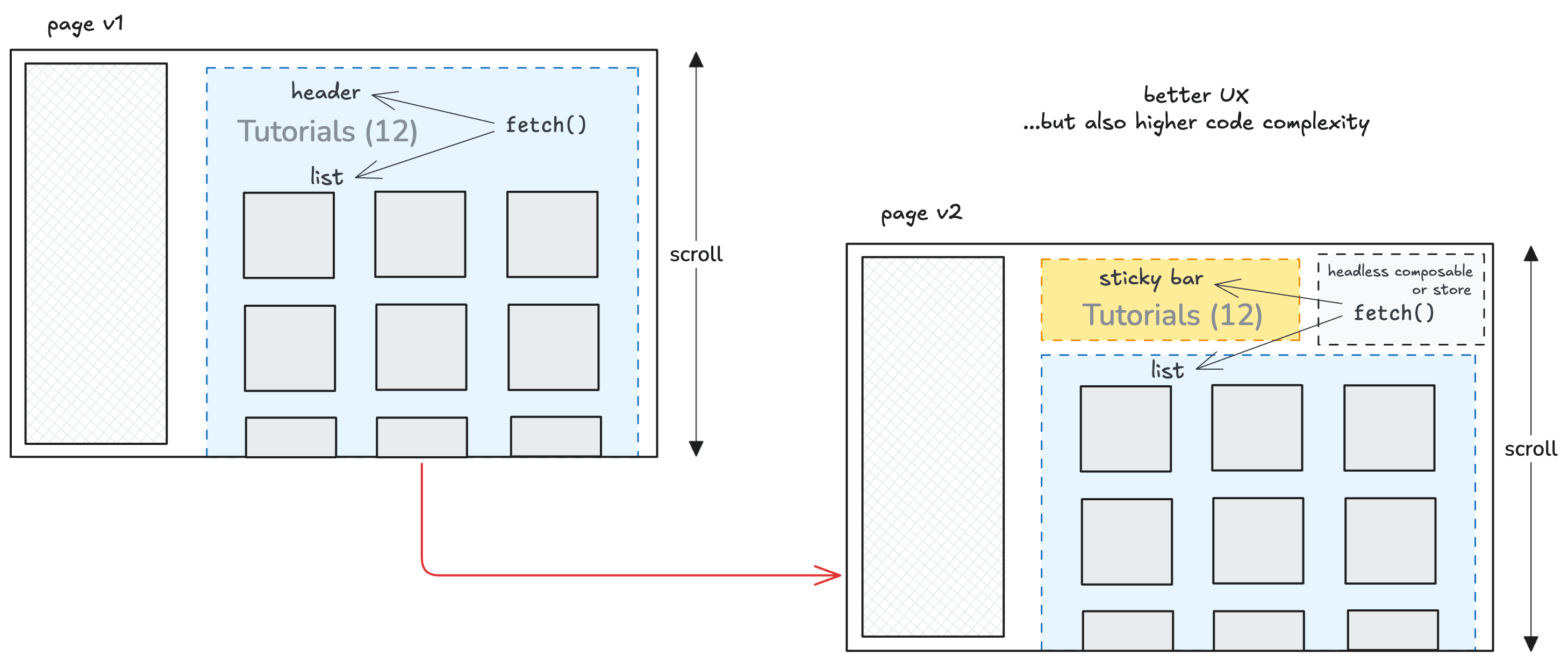

I needed to make the dashboard tab pane stick to the top of the page regardless of the content height of individual tabs. Scrollable panes suck, so the page itself needed to scroll.

The problem was that data (for example, a list of tutorials) was fetched by the pane itself, which also contained filtering sub-tabs and list rendering. You couldn't simply split the pane into two components without making them communicate.

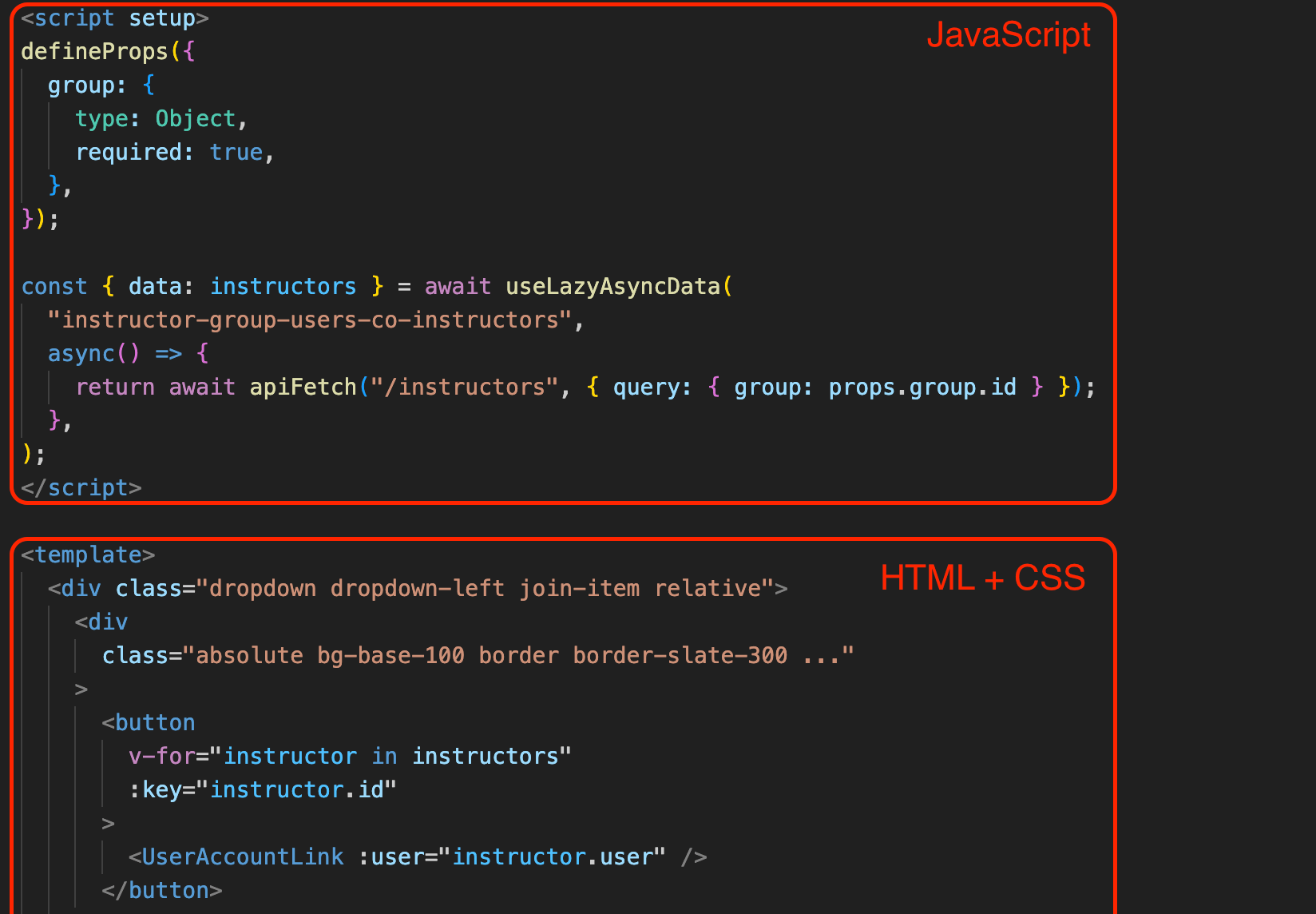

After using Vue for a few years, I know how to solve this with composables (or even a store). But for historical reasons - and for simplicity - many parts of the codebase still use an old jQuery-style pattern: fetch data in the <script> block and render it in the corresponding <template> block of the same component.

When I asked Claude Code to split the pane into a filter bar and a list, it failed miserably. It started with a literal split into two sibling components and a shared parent that fetched data and passed it down. That didn't solve the layout problem at all: the data would have needed to be fetched even higher up, and prop-drilling through multiple layers would have been a mess.

I intentionally didn't explain this and simply asked Claude Code to continue and make the layout change. It ran into the same wall I expected and tried another approach: a provide/inject trick. But the provider would have had to live far too high in the hierarchy - almost at the app level - and Claude Code couldn't pull it off. (It might be possible, but I wouldn't choose that route anyway.)

Eventually, I directly asked Claude Code to introduce a composable that would bind the filter and list together without assumptions about their DOM placement. That worked like a charm. The change was simple, and Claude Code nailed it in minutes. But for that to happen, I had to know what to ask for - knowledge that came only from prior Vue experience and many hours spent learning the framework.

A vague "product prompt" like "split this component, make one sticky, leave the other on the page" just doesn't work. And it may never work. I honestly wonder what problems people on X are solving when they claim to successfully use multiple fully autonomous agents.

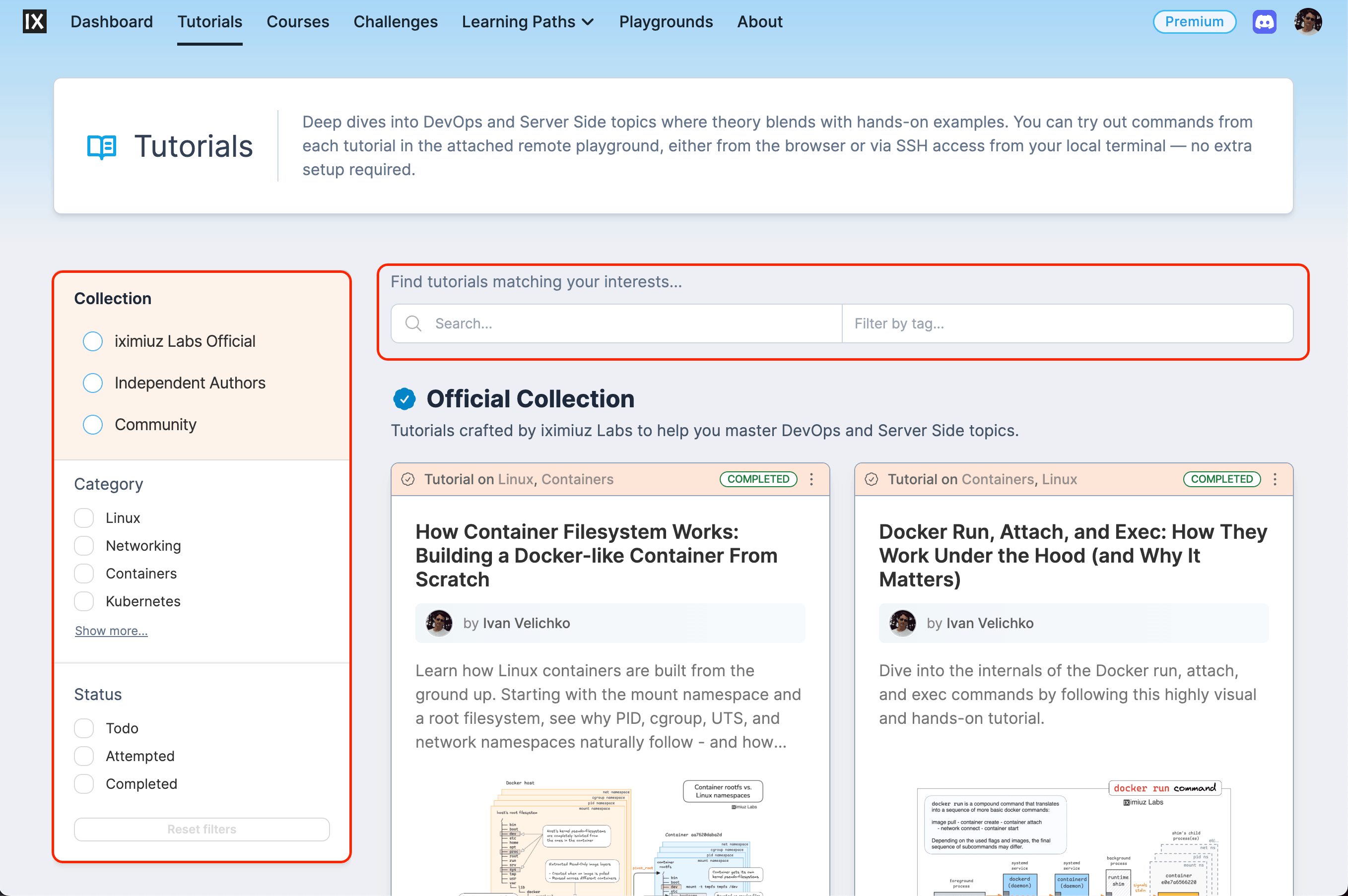

A trivial frontend change: catalog layout redesign

Here's a simpler example that still shows where agents shine. I needed to move the sidebar to the left and split the search/tag box out into a new horizontal search bar.

I gave Claude Code a high-level product prompt, and it predictably failed. Then I broke it down:

- Move the sidebar to the left (success)

- Split out the search box (success)

- Turn it into a horizontal search bar (semi-success)

- Make the search bar sticky on mobile (fail - wrong positioning, horizontal scrolling, no luck auto-fixing even with Chrome DevTools MCP)

And that was just the beginning.

After adjusting the layout, I needed to show all collections on the same page: iximiuz Labs official, independent authors, and community. At that point, the backend was serving only two collections, so Claude Code hard-coded a binary if/else instead of a generic loop. Even funnier, it removed the Independent Authors collection from the page entirely because the API didn't seem to support it. I insisted it be restored and the API extended instead - but this was clearly not autonomous coding.

Once again: "product prompts" don't work yet, and I don't expect them to anytime soon for non-demo projects. There are exceptions - greenfield projects, smaller scopes, perfect test suites - but those are outliers. Real-world projects are messy, full of hidden assumptions, conflicting requirements, and bespoke tools that no training set can fully capture.

What does work is the traditional approach: the developer knows what needs to be done and how. The difference is that instead of spending hours implementing it, you can now send agents to do it. When positioned properly, they're blazing fast.

Just be careful how you chunk your tasks. Assignments that are too large produce unusable results; tasks that are too small make agent overhead (loading the context and verifying the change) outweigh the payoff.

After I reworked the first catalog (a full day of back-and-forth), porting five others "by analogy" took just another 30 minutes. Without an agent, that would have been another full day of dull work.

General observations

- Claude Code produces a lot of copy-paste code instead of reusable components, despite explicit instructions to minimize duplication.

- It tends to optimize for satisfying the latest prompt, without seeing the bigger picture or consistently following project-wide style - unless everything happens in the same file.

- It is extremely success-oriented: skipping tests, removing features, or ignoring requirements - whatever it takes to declare the job done.

- It performs poorly on high-level product prompts and requires a human who can decompose problems and reason about solutions.

- It is incredibly effective when you already know exactly what needs to be done and how (10x–100x velocity).

- It excels at investigating reproducible bugs - those with tests, clear repro steps, or massive logs that a human would otherwise skim for hours.

- It changes development dynamics: tests, refactors, and cleanups that once felt too expensive now become cheap - and more valuable than ever, because agents will happily replicate whatever code they see, good or bad, and without automated tests there is no way to keep your code working in the new fast-paced development reality.

On the claimed loss of flow state

The flow state is still there. I often read claims that herding agents breaks deep focus, once the most productive state for programmers. I still experience it frequently - but my focus has shifted a level or two up. Instead of juggling code blocks, I think in terms of modules, requirements, and missing pieces.

I find it even more rewarding. As much as I love(d) coding, I love good end results just as much. For me, the magic of building software is still very much alive.

Instead of a conclusion

In my opinion, most of the hype - "you can now build a SaaS in a day" or "anyone without prior experience will soon build personalized software" - is unjustified. From my perspective, things haven't changed dramatically since 2023. What has changed is the superpower engineers now have. We're just too busy building to hype it.

Another common theme is FOMO. Between July and October, I was deeply focused on iximiuz Labs content. I used AI extensively outside of development, but my fear that coding agents would make me obsolete as a software developer kept growing. After burning through a few million tokens on code generation, that fear is gone - not because AI performed poorly, but because I can now confidently dismiss 80% of exaggerated claims on X and have a solid intuition for how to use coding agents effectively.

Hands-on experience still matters enormously, both at the micro and macro levels. On the micro level, you need to recognize code smells, suggest better structures, and spot risky changes (data formats are especially dangerous). On the macro level, you need to translate product requirements into concrete implementation tasks and decompose them into steps sized to an agent's capabilities.

Most of the code added to iximiuz Labs in January was generated by Claude Code, and I'm grateful for it. But I'd argue that all of it was still authored by me. Left unattended on a real production project, Claude Code - and other agents - are nowhere near as capable as people on X would like you to believe, no matter how many rules, skills, or planning documents you throw at them.

Level up your server-side game — join 20,000 engineers getting insightful learning materials straight to their inbox: